When the Nikon Series E 75-150mm arrived at my doorstep earlier this year, I almost forgot it was supposed to arrive at all. The lens was a part of a Nikon FA review package sent to me by James, and was originally headed towards the junk bin at F Stop Cameras due to a minor bit of fungus on one of the internal lens elements. It was included just in case I felt moved enough to write a review on it. If I did, cool; if not, no worries – it was just another weird zoom lens. Suffice it to say, I wasn’t expecting much.

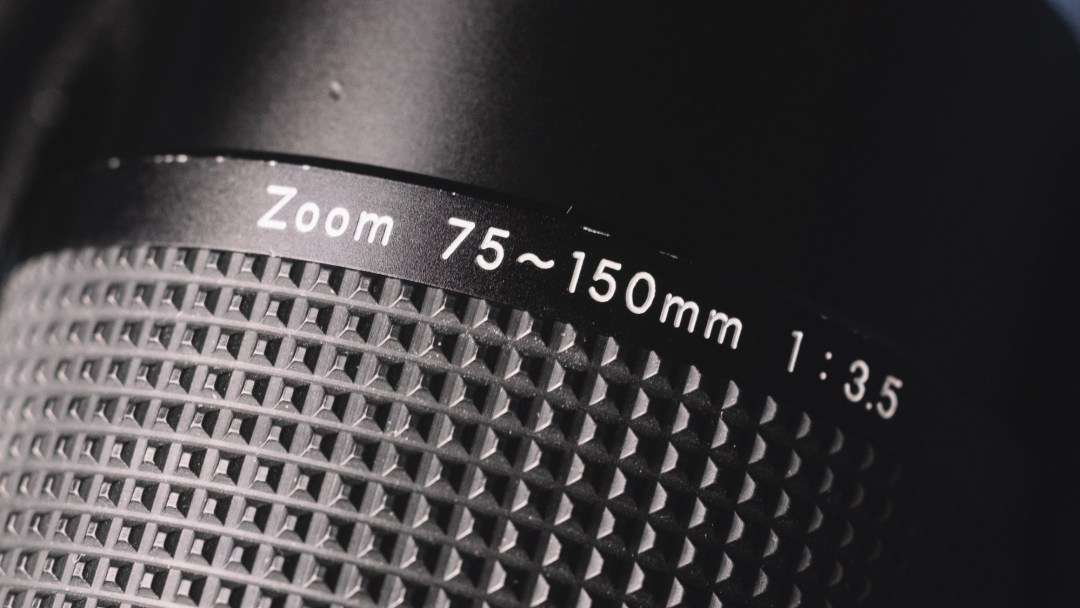

After six months with the lens, I realize that no matter if I expected the lens to be terrible, mediocre, or even great, I would’ve been wrong. Somehow, the Nikon Series E 75-150mm f/3.5 seems to exist beyond those descriptors. Even though it’s unglamorous and completely utilitarian both in its design and its imaging characteristics, it has somehow delivered all (read: ALL) of my favorite images taken this year. It has since outlasted the now-dead FA it came packaged with, pulled me away from my beloved Olympus Pen FT for most of the year, and has somehow found a near-permanent home on my Nikon F3. I’d call it a sleeper lens, but it’s a bit more special than that.

Unbeknownst to me, the Nikon Series E 75-150mm f/3.5 was, in its day, a truly special and renowned lens. It was a true classic back then (most notably used by Galen Rowell for his most famous photo), and was made for the consumer market but beloved by professional photographers for its unassuming versatility and quality. Today, it could represent the best value for money in the Nikon lens catalog. It was, and still is, one of the rarest objects in photography – a lens made for everybody.

The Background

The Nikon Series E 75-150mm f/3.5 was set up for success early. Even though it was formulated for Nikon’s budget-minded Series E line, it was designed by one of Nikon’s best minds, Yutaka Iizuka. Iizuka’s pedigree leading up to the design of this lens was impressive; he most notably helped design the groundbreaking Zoom-Nikkor 50-300mm f/4.5, one of the very first high-powered zooms made for 35mm still cameras. So when the company came calling for an inexpensive, but high-quality zoom lens, the brilliant Iizuka answered.

“Inexpensive” was certainly the most important word in the design brief for all of the Series E lenses, but this didn’t necessarily correlate to a drop in quality, as many people repeat in modern times. Quite the opposite – Nikon believed that good design would be able to withstand and overcome the cost-cutting measures put in place for the Series E line. This philosophy guided Iizuka through the lens’ design, which featured a simplified (for zoom lenses, anyway) twelve element in four groups structure optimized for a shortened zoom range of 75-150mm and a constant aperture of f/3.5. If the lens was any bigger or more complicated, it would be unwieldy and expensive; any smaller and it would be too demanding to manufacture and more expensive still. This specific design ensured that Nikon could save money and increase manufacturing volume while still having a lens which performed to their incredibly high standard.

The narrower zoom range also ensured high image quality. Its design could have been stretched to cover a greater focal range, but it was limited to 75-105mm to make sure that the lens didn’t sacrifice image quality at its extreme ends, as zooms often tended to do. The Series E 75-150mm’s uncommonly clean, sharp visual signature at every part of its zoom range as well as a versatile constant maximum aperture of f/3.5 gave credence to the claim that zooms could conceivably replace an entire set of prime lenses without sacrificing image quality.

The lens became a cult favorite among professional photographers seeking an easy-to-use, compact, and cheap short telephoto solution. It was portable in comparison to the big boppers of the day like the famed Vivitar Series 1 70-210mm f/2.8, and could conceivably cover portrait photography, landscape photography, sports photography, and general photography duties due to its stellar all-around performance.

Time, however, hasn’t been particularly kind to the reputation of the Series E 75-150mm zoom. Vintage zoom lenses have never had a particularly good reputation in today’s film photography renaissance, mostly owing to the vast improvement in zoom lens technology in the last twenty years, and because of the glamor of shooting prime lenses. The estimation of the Series E 75-150mm seems to be that the lens is simply Good Enough these days, and that its stellar reputation in professional photography circles is outdated. After using it extensively for the past few months, I can see where these arguments come from, but can’t disagree more about its utility. Although it doesn’t immediately dazzle, it is absolutely still one of the most usable, convenient, and dare I say high-performing short telephoto lenses out there, zoom or prime.

The Details

If there’s any prevailing strength of the Series E 75-150mm f/3.5, it is Yutaka Iizuka’s original design. The design was good enough to endure the initial cost-cutting, but it was also good enough to stand the test of time. To this day, the lens possesses a truly remarkable sharpness from corner-to-corner at every focal length that holds up even under heavy cropping. Distortion is minimized at either end of the zoom range, with minor pincushion distortion at 75mm and minor barrel distortion at 150mm. And I really do mean it when I say “minor” – in practice this really doesn’t affect most images barring critical architectural work, and even then a quick Lightroom adjustment will eliminate the distortion altogether.

The other strength of this lens is something uncommon to zoom lenses – bokeh. The proclamation that zoom lenses do not create good bokeh is usually one parroted by prime-lens obsessives, and while somewhat true, the repeated assertion does not apply to the Series E 75-150mm. Iizuka intentionally designed the lens to create smoother bokeh by reducing the amount of spherical aberration correction at close focusing ranges, a technique also used in the fabled Nikkor AI 135mm f/2 lens. This lens can paint bokeh with the best of them, which makes it usable for portraiture and close-up photography in ways that even many modern zooms cannot replicate, which makes the lens that much more versatile.

The beauty of the Series E 75-150mm is that all of its features come in service of practicality. Its compact design, good bokeh, and sharpness at every part of its focal range makes it an obvious choice for any shooter, professional or casual. I can see why professional travel photographers loved this lens back in the day – it’s a far more sensible choice if you’re not sure about what kind of image you’ll be running into. You simply don’t have to swap lenses as much, nor do you have to compromise by lugging around a heavy albatross of a zoom lens. All zoom lenses have this inherent advantage, but the Series E 75-150mm’s quality and practicality ensures that you’re also just as satisfied with the result as you would be with a prime lens.

While the lens is stellar in nearly every department, it does leave a little to be desired in a few key areas.

Optically, the lens suffers from pretty bad flare. Flare resistance is quite weak despite the design’s attempts to mitigate it, and images will tend to lose a huge amount of contrast if there is any amount of light that glances off the front element (note: this can, of course, be remedied by use of the Nikon HS-7 lens hood).

Build-wise the lens suffers from zoom creep, a problem that sometimes plagues “one-touch” zooms which feature a push-pull zoom action. Lenses which suffer from zoom creep have lost all friction over time, meaning that their barrels will tend to slide to their maximum or minimum focal length at the slightest provocation. Upon receiving my lens, the zoom creep was so bad that it just couldn’t hold itself at a constant focal length, so I had to remedy it by sticking a piece of electrical tape on the barrel to get it to stay put. It wasn’t a huge deal, but it was and is a major failing of the zoom design of this lens.

Barring those practical faults, there is one fault that might be a deal-breaker for some – it’s too practical. The lens’s zoom range of 75-150mm and maximum aperture of f/3.5 is respectable, but isn’t capable of the high-flying acrobatics of the Vivitar Series 1 70-210 f/2.8 or Minolta 70-210 f/4 “beercan” lens. And except for maybe its stellar bokeh characteristics, the lens’ rendering doesn’t immediately dazzle. It’s sharp and renders an incredible amount of detail at every focal length, but it doesn’t “paint” quite like other lenses, most notably prime short telephotos. The Nikkor 85mm f/2, 105mm f/2.5, and 135mm f/2 come to mind as truly beautiful lenses which have the edge on the Series E 75-150mm when it comes to image rendition.

The Bottom Line

Then again, the Series E 75-150mm wasn’t designed or produced in the name of beauty or extravagance; it was produced in the name of practicality. It’s a lens that earns its keep in the field, is made to be shot hard, and rewards handsomely those willing to learn its available focal lengths inside and out. It’s perpetually ready for you to take the next shot no matter the situation, which is something prime lenses just can’t do.

But perhaps the best thing about this lens is that it’s still inexpensive. The market hasn’t really decided how to feel about this otherwise nondescript lens from the early 1980s, so prices still range anywhere from $25-80 USD. If you see one in the wild, snap it up and don’t think twice about it. There’s really not much that can go wrong with this lens other than zoom creep, so you’re virtually guaranteed a high-quality, compact short-telephoto lens for cheap. And in my humble, totally out-of-touch opinion, I don’t think prices on these are going “to the moon,” as the kids say. Old manual focus zoom lenses are like ’90s autofocus SLRs; they’re unglamorous, utilitarian, and just dorky enough to evade the Sauron’s eye of internet influence. I don’t even think a beanie-clad, Squarespace-sponsored film photography Youtuber could make these things hip enough to be out of reach, and that’s saying something (I think).

The Series E 75-150mm could be labeled a “sleeper lens” and even a “cult classic” but I think those terms betray the original intent of the lens. This wasn’t designed to be a lens for those in the know – it was supposed to be a lens for everybody. Its greatness was on display from the start, and it was once enjoyed by quite literally every class of shooter. So if you find one, pick one up, maybe even tell a friend about it. A product this plentiful, this good, and this useful is too rare to pass up, and too beautiful not to share.

Shop for your own Nikon Series E 75-150mm on eBay

Find a lens at our shop, F Stop Cameras

Follow Casual Photophile on Twitter, Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

I can only confirm everything Josh has stated about this lens. One thing which could be added to the review is that the advanced Nikon FA has zoom exposure correction while metering, which makes this lens a great companion to this techno camera.