A few months ago I bought a Sony Walkman. Not the $3,000 WM1Z, which is the company’s modern, high-resolution digital music player and likely the greatest portable music player ever created. No, instead what arrived in my mailbox was the WM-F35, which at 33 years old is a few months older than I and plays cassette tapes.

While the WM1Z digital player has 250 gigabytes of storage, plays lossless audio that competes with the quality coming from a proper record player, upscales normal files to high-res quality and uses an HX digital amplifier, the tape player has an AM/FM radio. And it floats.

There’s not much comparison between tapes and hi-res digital audio. Even in their heyday, tapes suffered a reputation for low quality. But here I am, opening my Walkman and dropping in a well loved and mildly warped copy of The Way it Is by Bruce Hornsby and Range. As the tape groans to life, I wonder, “Why did I spend 100 euros on an ancient instrument that plays an obsolete, nearly dead format? Why am I spending actual money on cassette tapes that come shipped in cracked cases with faded liner notes?”

Maybe the answer lies in another historical artifact lying on my desk: the Agfamatic 2008 Pocket Sensor 110 film camera.

I see many similarities shared by these two relics. They’re both basic versions of more sophisticated products made by their respective companies. Both are prioritized for portability and ease of use. Both use outdated cartridges, the Walkman takes cassettes, and the Agfa Agfamatic 2008 Sensor takes 110 film. And in the context of usability, both can be a bit of a chore to enjoy in 2020.

But camera people live here in this CP tent, so I’ll focus on the picture machine. Maybe along the way I’ll find answers for both.

What is the Agfamatic 2008?

In 1972 Kodak released their new 110 “pocket system” film format. This 13x17mm film was housed in a small 24-exposure cartridge, didn’t require rewinding, and made loading easy for anyone with at least one arm. In the mid-seventies Munich-based film company Agfa became the first third-party company to offer both film and cameras for this new format.

The Agfamatic 2008 Pocket Sensor was the first camera to use Agfa’s “ratchet” operation system. The camera opened to the left by sliding a switch on the bottom. Once a photo was taken, the camera has to be pushed back together and out again, which advances the film and cocks the shutter. The noise the camera makes during opening and closing led to it being called the “ritsch ratsch” camera in Germany. Costing only 105 Deutschmarks (about 60 US dollars) it could fit in the budget of almost any family.

Another sliding switch unlocks and drops the film door, allowing the photographer to drop in a film cartridge. After closing it, a few ratchets of the camera advances the film to its starting frame. No amount of closing and opening the camera moves the film forward until the shutter has been triggered, a convenient feature considering that the camera is frequently closed and opened without taking a photo.

It has a 3-element Color-Agnar 26mm lens that is fixed at f/9.5, and two shutter speeds: 1/50 of a second and 1/100 of a second. A switch on the top of the camera selects the shutter speed, which is illustrated either as a cloud or the sun. Focus is fixed between 1.2 meters and infinity. The camera also came with a detachable flash bar and had a bright viewfinder with big parallax markers.

It’s a basic camera to say the least. The only decisions photographers are able to make are what film they shoot and which of two shutter speeds they snap with.

Of course simplicity of operation isn’t the camera’s only strength.

I came across the camera in the junk bin of a camera store. Attached to it was the original flashbar (which I later learned didn’t work.) It was this design that first caught my eye – it’s just a cool looking camera. It’s a mix of chrome and plastic that perfectly dates it to the mid-seventies, with a vague Bauhaus influence and the big red shutter button that screams AGFA. Believe it or not, this camera actually won the iF Product Design Award in 1974.

If you’re into tactile things, then this camera scratches that itch. It’s a product whose unique operation is part of its enjoyment. Occasionally I would pick it up just to hear the “ritsch ratsch” from opening and closing, the sound turning into a tiny joy button.

Noticing the absence of a price tag, I asked the store clerk how much he wanted for the camera. He looked at it and with a slight shrug, said five euros.

Out and about with the Pocket Sensor

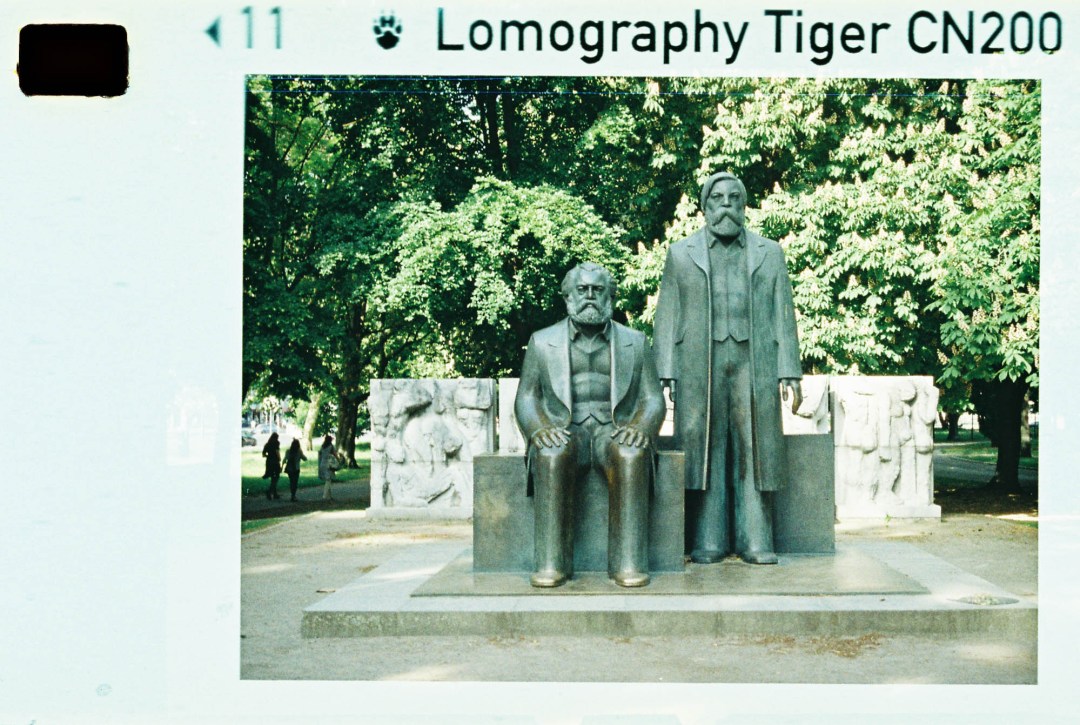

It wasn’t long after walking out of the camera store that the thought hit me: “Do they even make film for these cameras anymore?” I was relieved (but not surprised) to see that Lomography still offers a number of films loaded in 110 cartridges. This includes films only made for 110, like the Color Tiger 200, Orca 100 and Lobster Redscale, plus more universally available Lomo films like Metropolis and Lomochrome Purple. There’s even a 110 slide film for seriously adventurous masochists.

Something happened between looking up available films and actually purchasing some. Other cameras got in the way and by the time I finally purchased a three-pack of the Color Tiger 200, six months had passed. Spring was springing in Berlin and with more sun and the city cloaked in green, a punchy color negative film seemed appropriate.

Looking back at the first day that I shot the Agfamatic makes me laugh. I actually took a light meter with me to see how close I was getting to f/9.5 and the two shutter speeds. It felt like eating at a McDonalds in a tuxedo.

I learned quickly that with cameras like these you just can’t care that much. I mean, you could. You could actually take the time and effort to take properly exposed photographs with this camera. But it would take a lot of time and grind down your psyche in the same way that does tunneling out of prison with a plastic fork.

I don’t think that’s what the camera’s creators had in mind, and it’s certainly not the ethos behind the film that Lomography produces. So I changed my approach, began carrying the camera everywhere, and snapped away without any care for the exposure beyond asking myself “Is it sunny?”

That’s pretty much it. Choose clouds or sun, compose, snap, klitsch klatsch and repeat. I imagine it was completely perfect for anyone who didn’t need to understand photography, but still wanted photos to remember trips to Mallorca. (Fun fact: every German is required by law to vacation on Mallorca.)

Portability is always a topic when it comes to photographic equipment. In that regard, the Agfamatic is probably the most portable film camera I’ve ever used. As a small thin rectangle, it fits comfortably into everything from a pair of jeans, the inside pocket of a jacket, maybe even inside a really tight sock.

So it’s small, somewhat stylish, completely without technical capability, and it makes a cool noise. And you’ll never need to replace the batteries since it doesn’t take any. And it’s cheap. But what about image quality? I think we all know where this is going.

Here we meet the perfect storm needed to create imperfect images. A consumer grade film of unknown birth cut to the equivalent of 16mm film and exposed in a fixed-focus camera seemingly designed to miss exposure. And sure enough, it usually does. Photos are almost always under or overexposed, which is more a testament to mathematics than it is a knock on the camera.

I knew this when I dropped the film off. I was lucky that the neighborhood lab was able to process and scan the negatives. I was even luckier that they didn’t charge extra for the unique format processing like many other labs do. Ironically, when I received my scans, they were in 16-bit TIF format, which is a little funny all things considered.

Huge scans allowed me some flexibility with correcting some highlights and shadows, but there’s no denying that almost every photo was as soft as satin. It’s not easy to know by how many stops images are under or overexposed, but the film doesn’t seem to enjoy too much latitude in either direction. But when the stars aligned and images were properly exposed, colors were punchy, vibrant and warm. Color Tiger reminds me a lot of Fuji C200 and Agfa Vista, which is probably why I liked the images that came back.

I should mention that there are a few 110 cameras that have a greater amount of sophistication, including the Pentax Auto 110 and the Minolta 110 Zoom, both of which have interchangeable lenses. It’s highly likely that these cameras will produce more technically correct photos. But I really struggle thinking it’s worth going down that road. If the devil-may-care approach to this format is one of its strengths, don’t luxuries like variable f-stops and a range of focal lengths take away from that? If you’re using an SLR, why not just shoot 35mm and enjoy the countless advantages it has over 110 film?

Final Thoughts

There’s just no debating it. 110 film sucks. At least from a photographic purists perspective. Its tiny image area nerfs resolution and makes it impossible to print without special equipment. The cameras that use it are almost always cheaply made and devoid of features. Images are soft, rarely in perfect focus and with the basic cameras like the Agfamatic, correct exposure is a friend that only visits a few times per roll. And these are just the disadvantages present when 110 was still popular. There are plenty of new, modern roadblocks to shooting 110. Film processing, scanning, and the prices for said services. With 110 film in today’s world, at the end of the day we’re spending more money to receive lower quality images.

But along with murder hornets, 110 is having a moment in 2020. YouTube randomly started flooding with reviews of 110 cameras, and while it’s hard to see these cameras entering into a bubble similar to prosumer film point and shoots, Lomography has likely seen 110 film sales rise in the last weeks. And that’s a good thing. They’re almost single-handedly keeping 110 alive, and we should celebrate all film formats, if only in remembrance of those that have fallen. Pack film and disc film long ago passed to dust, and 620 is on life support.

Yet like tape cassettes, 110 endures. The most logical explanation would be that the cameras are extremely cheap and using them is a virtually thoughtless experience. But there’s likely something more to it than that. It’s different, for one thing, and the lack of control over the images actually feels a bit liberating. Just as in other instances where I’ve used what I call “anti-precision cameras” (the Zenit-E for example) the photos came back with a certain distinctiveness.

So to the answer of the big question – “Why?”

Like using an old Walkman, the Agfamatic 2008 is all about the experience. You enter into that experience knowing the limitations and obsolescence of the medium. In fact, that’s most of the motivation. To connect with something “else.” Life is cheaper and more convenient when I use Spotify on my phone. When I plug my headphones into a tape player, it’s in rejection of convenience. The same can be said for the 110 format generally and the Agfamatic specifically.

Get your own Agfa Agfamatic 2008 Pocket Sensor on eBay

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

This made me smile. I’m old enough to have coveted the Pentax Auto 110 when it came out, and I bought one recently in a charity shop for less than it’s already cost me in film and processing.

And it’s rubbish; although it has more sophisticated exposure control than your Agfa, and a lens you can focus, the essential, ineluctable uselessness of 110 film renders all finesse irrelevant. Without a pressure plate, the film is free to flap about in the back of the camera, so you can align your split image as precisely as you like and still not have the faintest idea whether the film is the same distance from the lens as the focus screen. The fixed-focus lens in the Agfa at least has the decency not to pretend.

None of this has stopped me hankering after Agfa’s premium offering, the A110. Like you, I love the red-button Agfa aesthetic and the James Bond-y ritsch-ratsch mechanism. It still won’t take pictures worth a damn, though. And, so far, I’ve managed to resist the urge.