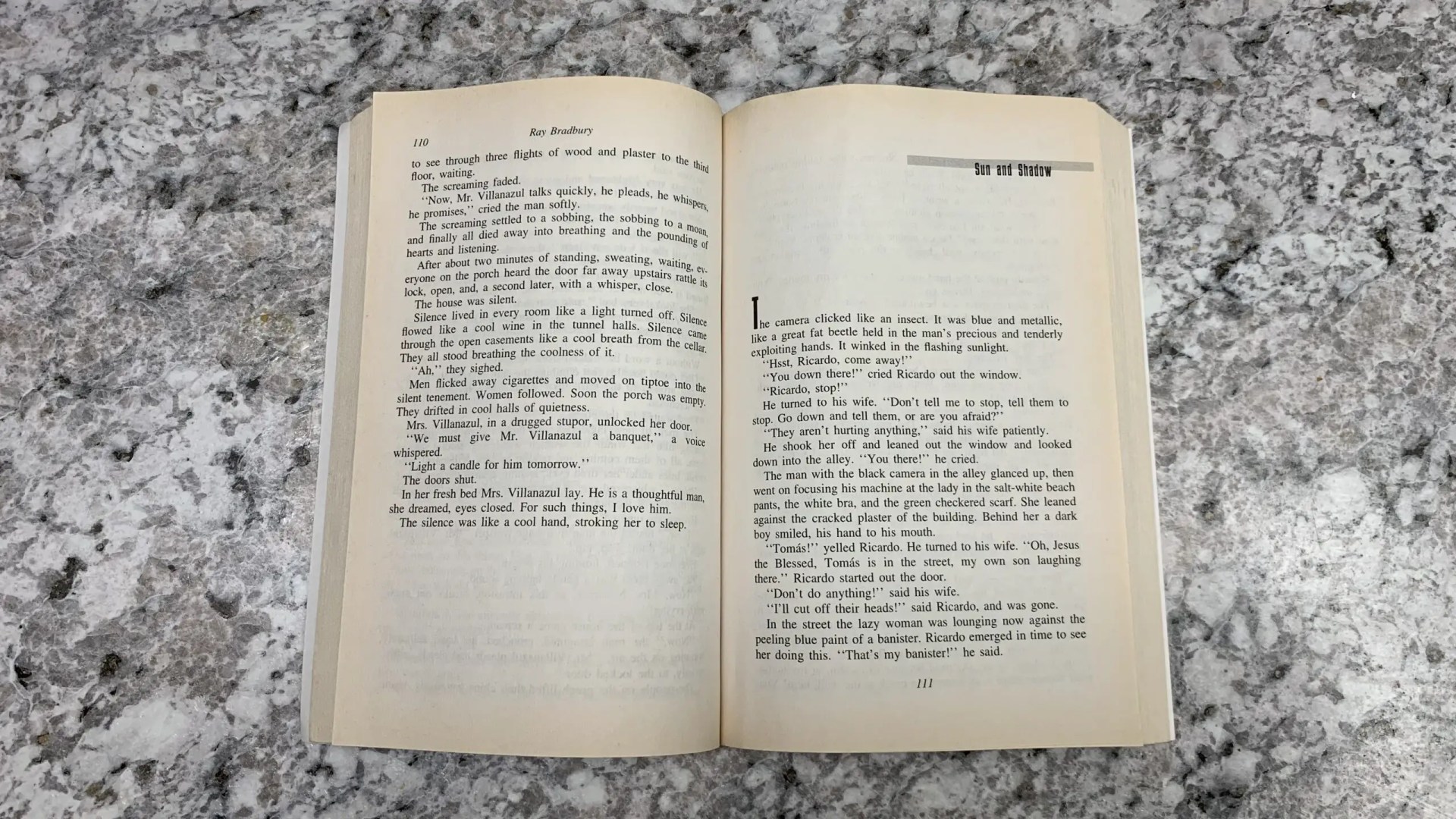

Reaching us from 1953, Ray Bradbury’s short story Sun and Shadow should be required reading for anyone who aspires to any level of editorial or street photography. It beautifully articulates the tension that I’ve often felt about photographic cultural appropriation, about the ways that photographers boldly and often carelessly photograph the people of the world as if they were created solely to exist in our cameras.

In Sun and Shadow, Ricardo Reyes, a man in a Mexican village, wages war against a fashion photographer who, in Ricardo’s view, is engaged in unforgivable photographic appropriation.

The story’s opening paragraph is intended to align the reader’s allegiance. In it, Bradbury describes a clicking camera held in the “tenderly exploiting hands” of a photographer. We may not know it yet, but by these words the reader should suspect Bradbury’s position; that the photographer exploits not just the camera, but much more besides.

From the window of his village home, Ricardo watches in annoyance as the photographer uses Ricardo’s alleyway as a backdrop. The photographer positions his fashion model subject against the cracked plaster of the building opposite Ricardo’s. He places her delicately against Ricardo’s own banister, with the weathered paint so artfully peeling. He positions Ricardo’s own son, Tomás, in the alleyway, within view of the camera’s lens. This is the final straw.

Ricardo shouts out the window to the photographer and model. “You there!”

Ricardo’s wife, Maria, embarassed, urges him to stop. “They’re not hurting anything.”

Storming out the door, Ricardo replies to his wife with Bradbury’s exaggerated sense of humor.

“I’ll cut off their heads!”

When he reaches confrontation range, Ricardo tells the photographer to get away from his house. The photographer assures Ricardo that it’s okay, that they’re only making fashion photos. The photographer is sure that this argument will work. He will tell Ricardo that they’re taking photos and Ricardo, like hundreds of others before him, will understand and let them get on with their work.

Ricardo won’t allow it, and he makes his point:

“You are employed; I am employed. We are all employed people. We must understand each other. But when you come to my house with your camera that looks like the complex eye of a black horsefly, then the understanding is over. I will not have my alley used because of its pretty shadows, or my sky used because of its sun, or my house used because there is an interesting crack in the wall, here! You see! Ah, how beautiful! Lean here! Stand there! Sit here! […] Oh, I heard you. Do you think I am stupid?”

Ricardo eventually berates the photographer until, exasperated, the photographer flees the alley. The battle has been won but the war is not ended. Ricardo wants the man gone not just from his alley, but from his entire village.

When the photographer tries unsuccessfully to pay Ricardo to leave him alone, and then announces loudly to his model that they’ll go take pictures on the next street over where earlier he’d noticed “a nice cracked wall there[…]”, Ricardo announces (louder still) that he’ll follow them.

Keeping pace with the fleeing photographer and his model, Ricardo once more makes his point.

And this paragraph, I think, is the heart of the argument. Ricardo wants his family and his friends and his village, his life and his place in the world, to be seen not as props, but as people. He demands no less.

“Do you see what I mean? My alley is my alley, my life is my life, my son is my son. My son is not cardboard! I saw you putting my son against the wall, so, and thus, in the background. What do you call it – for the correct air? To make the whole attractive, and the lovely lady in front of him?”

“We are poor people,” said Ricardo. “Our doors peel paint, our walls are chipped and cracked, our gutters fume in the street, the alleys are all cobbles. But it fills me with terrible rage when I see you make over these things as if I had planned it this way, as if I years ago induced the wall to crack. Did you think I knew you were coming and aged the paint? Or that I knew you were coming and put my boy in his dirtiest clothes? We are not a studio! We are people and must be given attention as people. Have I made it clear?”

Here, Bradbury has broached the subject of class and economics. Ricardo is poor. By contrast, the photographer and his model, with the hat boxes and makeup cases and assistants and expensive gear, must be rich. Bradbury shines a light on the power dynamic at play here, and the cultural looting done by traveling photographers who spare no expense for the perfect background or the artfully weathered wall, or the beautifully devastated face. The cracked hands of the sweatshop worker in Sri Lanka, or the blood-rimmed eyes in the blackened face of the coal-miner. The blistered feet of the man pounding pans in the streets of Kolkata for less money per day than an American would accept for a minute’s work. The photographers go out to hunt for the underpaid of the world, before returning to “civilization” to collect their pay.

But the photographer in the story isn’t listening. He’s moving his production along to the next alley. Once there, he comes across some colleagues shooting their own fashion shots. Here, Bradbury sprinkles his sense of humor, as the photographer greets his irreverent colleague and apprises him of the situation.

“How you doing, Joe?”

“We got some beautiful shots near the Church of the Virgin, some statuary without any noses, lovely stuff,” said Joe. “What’s the commotion?”

“Pancho here got in an uproar. Seems we leaned against his house and knocked it down.”

“My name is Ricardo. My house is completely intact.”

To this point in the story, it’s not perfectly obvious whether Ricardo is a fanatic lunatic or a reasonable man simply taking a stand against what he sees as an injustice. Bradbury presents the counterpoint to Ricardo through a number of characters within the story. These assert that the photographers aren’t doing anything wrong, that they’re simply making a living.

Ricardo’s own son laughs happily with the photographer. Ricardo’s wife tells him to leave them alone, saying in no uncertain terms that “they aren’t hurting anything.” When the photographer positions his model in front of a local shop, one which possess a “nice antique wall[…]”, Ricardo is stunned to find the shop owner watching the photo shoot with mild amusement.

“Jorge! What are you doing?” […] “isn’t that your archway? Are you going to let them use it?”

“I’m not bothered,” said Jorge.

Ricardo shook his arm. “They’re treating your property like a movie actor’s place. Aren’t you insulted?”

“I haven’t thought about it,” Jorge picked his nose.

“Jesus upon earth, man, think!”

“I can’t see any harm,” said Jorge.

But seeing that no one is going to stop the injustice, Ricardo takes action. As the photoshoot continues, he surreptitiously positions himself for the next salvo.

The photographer directs the model to pose this way and that, delicately composing his shot for the maximum effect, and just as he’s about to fire the shot, Ricardo bounds into frame and drops his pants.

“Oh, my God!” said the photographer.

Some of the models squealed. The crowd laughed and pummeled each other a bit. Ricardo quietly raised his pants and leaned against the wall.

“Was that quaint enough?” he said.

The plot of the story continues in this way for another page or two (the entire story is only eight pages long). Ricardo thwarts the cameraman by dropping his pants whenever a photo is attempted, all while a growing crowd of his fellow villagers look on bemusedly.

The photographer soon sends his assistant for a policeman. When the unhurried policeman arrives, he assesses the situation and sees no fault. Ricardo is simply standing there, naked. And in the policeman’s estimation, there’s nothing wrong with a man of the village standing there with his pants down.

They argue the point, but Ricardo has found allies in the villagers and policeman. When the photographer finally gives up, he tells his models “Come on, girls, we’ll go somewhere else.”

Ricardo is ready with a victorious reply.

“France,” said Ricardo.

“What!” The photographer whirled.

“I said France, or Spain,” suggested Ricardo. “Or Sweden. I have seen some nice pictures of walls in Sweden. But not many cracks in them. Forgive my suggestion.”

As the story ends, the photographer and his models retreat down the street toward the docks and Ricardo watches in satisfaction. He relives the moments before and plans his evening ahead. Here, Bradbury uses gorgeous lyrical writing to remind us of his position. That the world is not made for just some of us, it is here for all of us, and we are all equally deserving of it.

Now, Ricardo thought, I will walk up the street to my house, which has paint peeling from the door where I have brushed it a thousand times in passing, and I shall walk over the stones I have worn down in forty-six years of walking, and I shall run my hand over the crack in the wall of my own house, which is the crack made by the earthquake in 1930. I remember well the night, us all in bed, Tomás as yet unborn, and Maria and I much in love, and thinking it was our love which moved the house, warm and great in the night; but it was the earth trembling, and in the morning, that crack in the wall. And I shall climb the steps to the lacework-grille balcony of my father’s house, which grillwork he made with his own hands, and I shall eat the food my wife serves me on the balcony, with the books near at hand. And my son Tomás, whom I created out of whole cloth, yes, bed sheets, let us admit it, with my good wife. And we shall sit eating and talking, not photographs, not backdrops, not paintings, not stage furniture, any of us. But actors, all of us, very fine actors indeed.

By the end of the story, Ricardo is confirmed as a quiet hero. As the photographers flee and Ricardo pulls up his pants, the villagers literally applaud him.

Bradbury wrote this story in 1953. At that time, photography as a mainstream middle-class pursuit was relatively new. The Leica M3 didn’t exist yet. Most people didn’t know what an SLR was. Kodak hadn’t yet begun monetizing our living memories as “Kodak Moments.” And yet Bradbury was already writing about cultural photographic larceny.

I shudder to think what he’d write about the era of smartphone cameras, and Instagram and TikTok. An era in which travelers (often wealthy ones) seek out the “authentic” places (often code for “poor”), stand in line with dozens of other “photographers” and slice away their little piece of someone else’s world for display on social media. All without ever really interacting or experiencing the true cultures of the people whose land they’re shooting.

Don’t get me wrong. There’s no crime in photographers of a majority culture photographing people of a minority culture, or the other way around (though this happens far less often). That’s called cultural exchange, and it’s good.

But I think the critical judgment of whether something is cultural exchange or cultural appropriation should be held in the hands of the minority. It’s the duty of the majority to listen to the minority. And if any one member of a minority takes exception to the actions of anyone of the majority, that should be enough. Just one voice calling out for justice should be enough for the majority to listen, as happened in Sun and Shadow.

If, in the story, Ricardo had not existed, there would have been no conflict. The photographers would have absorbed the Mexican village into their photographs and carelessly jetted away. No one in the story, besides Ricardo, thought that the photographers were doing any harm.

Ricardo was the one voice. The one protesting minority voice amongst his indifferent fellows.

“Am I the only one in the world with a tongue in my mouth?” said Ricardo to his empty hands. “And taste on my tongue? Is this a town of backdrops and picture sets? Won’t anyone do something about this except me?”

No one in the story does, in fact, do anything about it. Ricardo is, in his own words, the “one man like me in a town of ten thousand,” who allows the world to go on as it should. “Without me,” he opines, “all would be chaos.”

Sun and Shadow currently appears in Ray Bradbury’s A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories

Buy A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories on Amazon here

Buy A Sound of Thunder and Other Stories on eBay here

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Youtube

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

I remember reading that story many decades ago, when I was a teenager who both read a lot of short stories and usually carried my Olympus OM10 in my schoolbag. It made me stop and think then too, I lived in a very photogenic part of the world, where there are lots of pretty old buildings and as a result I always thought twice whenever photographing too near to people and their homes.