Reading the pages of CP, it would be easy to assume that every camera made before the digital age was a masterpiece of design and function. But that’s so, so wrong. Today we enjoy the luxury of editorializing; we choose to write about special and interesting cameras. But for every Maitani masterpiece or incredible Rollei, there are ten or twenty real stinkers.

Take, for a start, the Konica AiBorg. Infamous among camera collectors, the AiBorg is one of many machines that promised to revolutionize camera design. At its release in 1991, Konica marketed the camera with such catchy verbiage as futuristic, black, and perhaps most curiously, ellipsoidal. The public decided these descriptors weren’t quite colorful enough, and quickly dubbed the AiBorg the “Darth Vader Camera.”

The camera epitomized the overwrought and confused design of the 1990s. It’s bulbous, plasticky, and coated in rubber. If that isn’t enough to put us in mind of Tim Burton’s Batman, the ridiculous obsession with excessive automation and silly gadgetry will. The AiBorg offers shooters a 39-exposure multiple exposure mode, and a long exposure mode capable of 100 hour exposures. Very useful.

It also doesn’t help that every button is hard to press and positioned as if Konica’s target consumer was a starfish. The multidirectional rocker switch on the back, right corner controls zoom, plus some other actions that aren’t entirely obvious. The function selectors for things like flash, multiple exposure, and other indecipherable modes are as intuitively marked as a Pharaoh’s tomb.

Konica missed the mark. The future they envisioned never came to be, and the AiBorg (thankfully) failed to change the game.

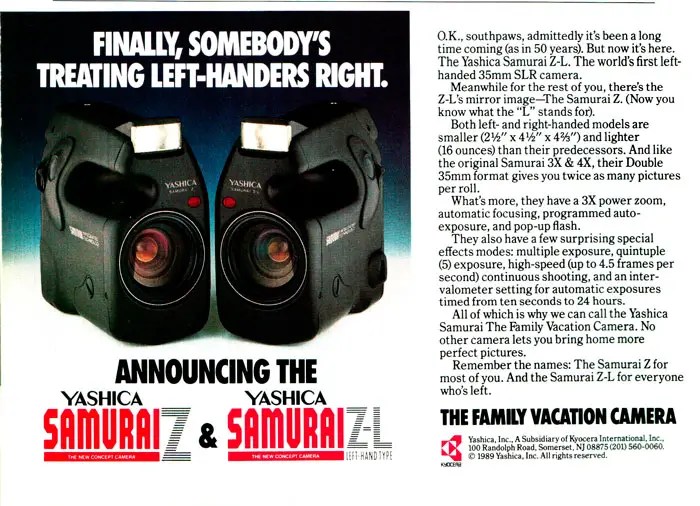

Four years earlier, Kyocera had tried a similar experiment. The brand’s designers started with the proverbial blank slate and attempted to design a revolutionary SLR camera. The result was the Samurai series, a range of half-frame 35mm film cameras whose chief claim to fame was their interesting physical shape.

Styled more like video camcorders of the time, the Samurai was unlike any stills SLR made before it (in shape, at least). It featured a fixed 25-70mm zoom lens, push button zoom controls, autofocus, built-in flash, and a surprisingly robust list of other stuff that looked good on a late-80s spec sheet. The camera was sold under both the Kyocera and Yashica brands, and was marketed as the ultimate vacation camera. They even released a left-handed version for the criminally under-served southpaw population.

The fact that SLR design didn’t change all that much in the twenty years following the Samurai’s release tells the rest of the tale. It just never caught on. Perhaps this had something to do with reliability and performance? An “RS” button on the camera resets the machine in the event its microprocessor locks up. This seems, somehow, suboptimal.

Or perhaps it was simply the fact that the standard SLR design had long ago been perfected. The Samurai was a classic case of breaking something that isn’t broken in order to fix it. Dumb.

Equally dumb was Kodak’s The Handle, an instant camera made in a period of time in which nearly everything was ugly (1977). At the time of its release, this camera was the ugliest object in the known universe. With no cohesive design ethos, it’s a plastic, clunky square with a rectangular protrusion jutting from the front.

The titular handle exists, presumably, because holding things is difficult and this makes it easier. As if this abomination to the senses wasn’t enough, Kodak did what Hollywood does; released a sequel that no one asked for. This equally repulsive camera was cleverly named The Handle 2, and it improved on The Handle in zero ways. Good job.

After just four years of production, Kodak was sued by Polaroid (inventor of instant photography) for patent infringements. Kodak lost. They were forced to cease all production of instant film cameras and instant film, and pay Polaroid $925 million. This happened in 1981, a time in which $925 million was more money than many countries’ GDP. In today’s money, that’s about $1.5 billion. Ouch.

Kodak was also required by law to pay damages for emotional distress in the amount of $20 to anyone who’d ever accidentally set eyes upon a The Handle.

Lest you feel we’re singling out some sad sacks, or if you happen to somehow love one of the mentioned cameras, rest assured we’re equal opportunity critics. These few machines aren’t the only gaffs we can think of. The past sixty years are packed with plenty of other photographic missteps.

The Leica M5 nearly sunk the company, financially, and the later R series machines have been described as softballs with a lens mount. And though these cameras are arguably among the better performing Leicas, people still have a hard time accepting their unusual designs.

Apple’s Quicktake 100 was, essentially, a Belgian waffle with a lens. Except a waffle makes better images.

The APS film format, intended to revolutionize film photography, was a massive expense that was fatally flawed before the first roll had ever left the factory. A smaller image area compared with 35mm film made it useless to pro shooters, and the nearly immediate advent of digital photography made it useless to amateurs. Bad planning, bad timing.

And let’s not dwell too long on the fact that Minolta invented the selfie stick as an accessory to go along with their “innovative” disc film camera, the Disc-7. Why, Minolta? Why?

Now don’t get me wrong; most of the cameras we’re lambasting are perfectly capable of making excellent photos. But forty years on, it’s not enough for a camera to make good photos. A film camera worth talking about in 2018 needs also to be well-designed, easy to use, and a treat for the senses. These rather unfortunate cameras remind us of just how special the truly special cameras are.

Got a camera you absolutely revile? Tell us about it in the comments so that we may also point and laugh.

Do you want one of these wretched cameras (or maybe a good one)?

Find them at our own F Stop Cameras

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Even as a kid, I thought the Kodak Handle was extraordinarily fugly. Looking at it now, I’m immediately reminded of my mother’s AMC Pacer. The Handle screams for some wood panelling. The 70s really were the nadir of design.

Also, the M5 to me looks more like a Zorki than a Leica. But I still wouldn’t kick it out of bed for eating crackers.