I’ve recently decided to take everything I know about photography, and my large collection of photography gear, and throw it all (as well as caution) to the wind.

In the 21st century film photography world we spend countless hours combing through forums, watching videos, reading articles (getting a bit self-aware here), and having conversations with fellow photographers, all to figure out what gear we should drool over next, or what niche camera will be smart to buy before they all vanish from the market. This tendency for gear obsession has recently reached a breaking point with me.

This article is the result, and it will combine a bit of review, a bit of opinion, and a bit of philosophical rambling. Hopefully, at the conclusion, you will come away refreshed and with a bit of clarity (like I have).

I will begin by laying out the gear that I used while on my journey toward centering my photographic soul.

First, the Nikon F. What can I say that has not been said already about this important piece of photographic history? I know that James reviewed it many years ago, and it’s been mentioned by some of the other writers of Casual Photophile several times since. For my purposes, I’ll lay it out as simply as possible; this camera, compared to what came out later in the Nikon F lineage, is as simple as you can possibly get.

The Nikon F is like an old Toyota Land Cruiser, it has the minimum features that you need, and that’s it. The camera is as utilitarian an SLR as any that you could possibly find. That being said, it has made some of history’s most important photographs.

The Nikon F went into space, it trekked through the Arctic, and it even saved stopped a bullet from ending Don McCullin’s life in Cambodia. This camera is not only the epitome of simplicity, but it also represents a quality of build and longevity that hasn’t been seen in modern camera systems in quite some time.

Next, I want to talk about my choice of lens. Why a 50mm? Simple. Everyone’s first SLR almost always comes with a 50mm lens attached to the body. It’s the standard focal length from the 1930s through today (though there is some argument to be made that the “standard” lens is changing to a wider angle these days).

Okay, but why the 50mm f/2? Why not a faster, fancier lens? Most of the 50mm lenses that would’ve come attached to SLRs in the film era would have been the faster, ubiquitous f/1.8. The spendy among us might have even splurged on the f/1.4 gem. But not me. I wanted my back-to-basics lens to be as bare bones as possible. So, it was the Nikkor 50mm f/2, specifically.

But while I admittedly chose Nikon’s slowest 50mm lens, that doesn’t mean that I chose the worst one optically, not by any stretch. The Nikkor 50mm f/2 is an overlooked, underrated piece from the legendary line of Nikkor manual focus lenses. There is something of a cult following around this lens, and the people like me who are a part of this small group have a tremendous love for the optical characteristics this lens offers.

The Nikkor 50mm f/2 was introduced in 1959, the same year as the Nikon F. It first debuted with a concave front element, as it was a carry over from the Nikon S rangefinder line of lenses. These lenses can be easily identified by the writing on the front of the lens, with 5cm being the indicator in place of the later common 50mm. No notable changes were made until 1972, when multi-coating was introduced to the glass.

In 1974, the close focusing distance was lessened from 0.6m (about 2ft) to 0.45m (1.5ft). When Nikon entered the AI era in 1977, the writing was on the wall for this lens with Nikon’s optical engineers. Then, in 1979, the 50mm f/1.8 Nikkor was introduced, promptly ending the twenty-years-long production run of the Nikkor 50mm f/2.

The optical formula of the 50mm f/2 is comprised of six elements in four groups, and this it retained throughout its entire production. It also has the smallest aperture range of the Nikkor 50mm lenses, with a minimum aperture of only f/16 and maximum at f/2. All other Nikkor 50mm lenses have f/22 as the minimum.

The aperture diaphragm consists of six blades, which is unusual in the Nikkor realm, since all of the other Nikkor lenses were made with an odd number of blades, with seven or nine being the most common. The bokeh produced by this six aperture bladed system has been described as “hexagonal” which is most certainly true, and I must say, for someone like me who doesn’t normally pay particular attention to the mushy, squishy background, I was thoroughly surprised by how nice this lens renders that space. I have seen people here and there online refer to this lens as the “Japanese Summicron” and I don’t think that I can disagree. Yes, Leica lords, there is a potential rival to the 50mm Summicron that is so beloved by M users, but I don’t think that sentiment is meant to be construed in that manner. I think what that moniker means, at least to me, is that what this lens lacks in aperture performance, it makes up for in sharpness and contrast.

The overall rendering characteristics of the lens itself is marvelous. It’s sharp, contrasty where it needs to be, and it portrays an overall classic touch to photographs that I don’t think many lenses can offer.

Finally, to round out the roll call, what back-to-basics film did I use?

When I was pondering this decision by looking at what film I had in my stock, the answer soon made itself clear. How much more basic can you get than Tri-X? Not just any roll of Tri-X, an expired roll of Tri-X Pan. I won’t get into how to shoot expired film, James already put in his two cents about the one stop for every decade rule in an earlier article. Since expired black and white film holds up better than expired color film, I simply decided to use the Sunny 16 method, shoot the film at its box speed of 400 and be on my way.

You may ask: Why Tri-X? My answer to that: Why not? Tri-X is old faithful, it’s tried and true, it’s the film that photographers will unanimously swear by (and I say all of this as a massive purveyor of the TMAX emulsion). Tri-X is the one film that you can count on for any kind of shooting. At box speed, this film is contrast heavy, yet still retains shadow details. Pushed two stops, the contrast increases significantly and that signature Tri-X look is on full display. There’s nothing fancy with Tri-X and that’s why I chose it. Its long lasting legacy as one of Kodak’s most enduring film stocks is unmatched, which is kind of bittersweet since I don’t hear many people outside of a certain age group talk about it too often.

Alright, by now, you may have noticed a building theme with what I’ve chosen to be the focal point. Yes, you would be right, everything I’ve talked about so far has been described as simple, utilitarian, or “just works”. None of those are bad things; quite the opposite. While I was out shooting this roll of Tri-X not once did I have a second thought about any of the images I took. I did what I had set out to accomplish; I focused on my surroundings, composed the photographs I saw as they happened, clicked the shutter, and on to the next.

One could describe this as a liberating experience. This is what photography (film or digital) should be all about; composing, waiting, deciding, clicking the shutter, and moving onto the next photograph. The purity of the process, being present, listening to the camera’s mechanical movements, feeling the weight of the camera body in your hands or on your shoulder while you carry it through the world. This is zen my fellow camera-holics.

It was only through experiencing this unique sort of camera clarity that I realized what I was struggling with in my photographic universe. Like most people, I’ve acquired, sold, and even traded dozens of cameras along the way. I’ve had several 35mm systems and several medium format systems, and I’ve even had them all at one time. But having multiple camera systems, no matter the format, have never helped me make photographs any easier. As I acquired more and more cameras, not only did I suffer from less shelf space, but my ability to grow into the photographer that I wanted to become was actually hindered by my gear acquisition syndrome.

You may be wondering, why randomly bring up G.A.S. in the middle of an article talking about going back to basics? Well, simple – I needed to force myself out of my comfort zone to see my own weaknesses. My weaknesses were within my own mind.

I’ll explain – in my quest for gathering a small group of SLRs that can do it all across different camera bodies, why couldn’t I just find an SLR that can do everything that I need out of the several that I have and downsize? I know everyone is different in this matter, but when it comes to gear, I do not like having gear that will mostly live on a shelf. I use my gear and I expect to get full use out of it as it was intended. Ultimately, these are professionally crafted tools. Some, I will concede, are collector’s pieces; looking at you Lenny Kravitz Edition Leica owners.

After writing the first draft of this article, I decided to take this moment of clarity and cleanse myself of the excessive gear that has plagued me. I have sold all of my 35mm Nikon bodies; Nikon F included. Why then, would I dedicate an entire article to a camera that I no longer own? I wanted to share my experience with using the most basic camera body and lens, a combination that allowed me to experience pure photography and helped lead to this moment.

There are some things the Nikon F lacks that could have enhanced the experience altogether, but it was only when shooting with it did I realize that these features could have actually refined my process of making photographs. I went through all of this to find out that I don’t actually need a library of gear to make the work I desire. Some people do, and more power to them. But for the other people who are like me and can’t stand to have an abundance of gear, this journey of going back to the bare minimum to realize what I realistically need for my arsenal, in this case a 35mm camera, was much needed and welcomed.

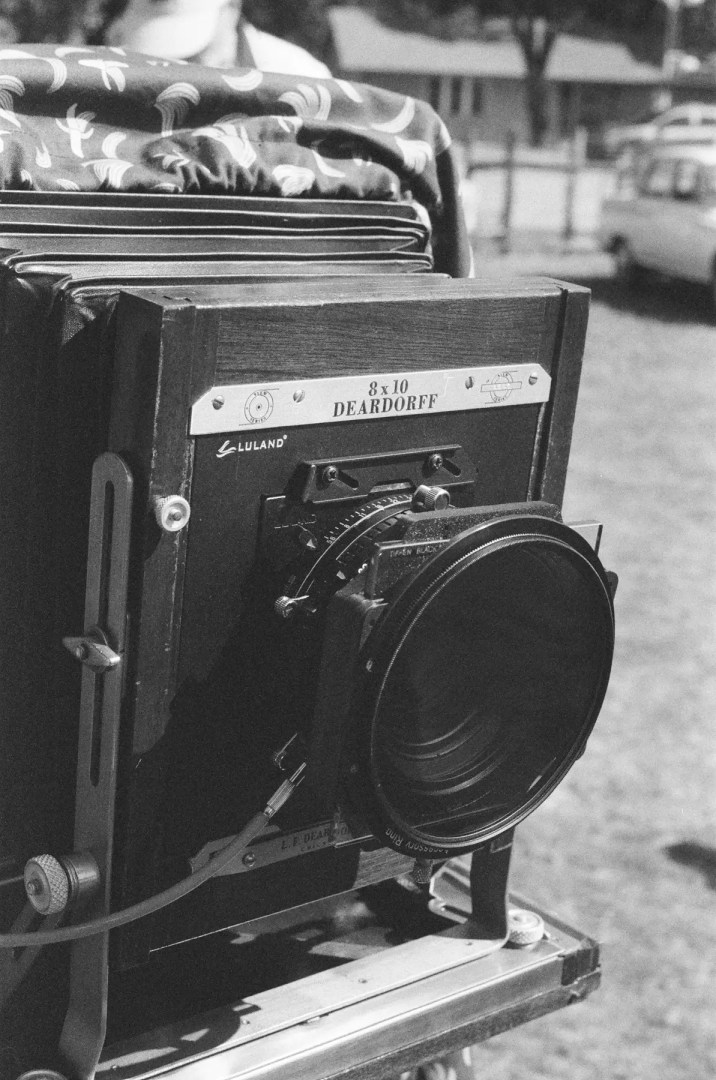

My 35mm slate is officially blank. Where to now? Do I find the end all, be all for my personal preferences? Do I switch over to an entirely new system altogether? Will James let us exclusively review large format gear? Tune in next time for another gear talking, shutter clicking, lens turning episode of Casual Photophile.

Browse for your own Back To Basics camera on eBay here

Search our shop at F Stop Cameras here

Follow us on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Youtube

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Great name.

Great review.

In this world we have to return to the classics, the basics of life for everything, … we need just to have a look to our situation now … 😉 we carry nothing with us at the end. If we carry something a Leica M3 or a Nikon F will still work several hundred years later, than a digital joke will be full of fungus.

This a great kit.

Me, I return also on basics with my M3, a Canon LTM 50mm 1.4 and … also the Kodak TriX 😉