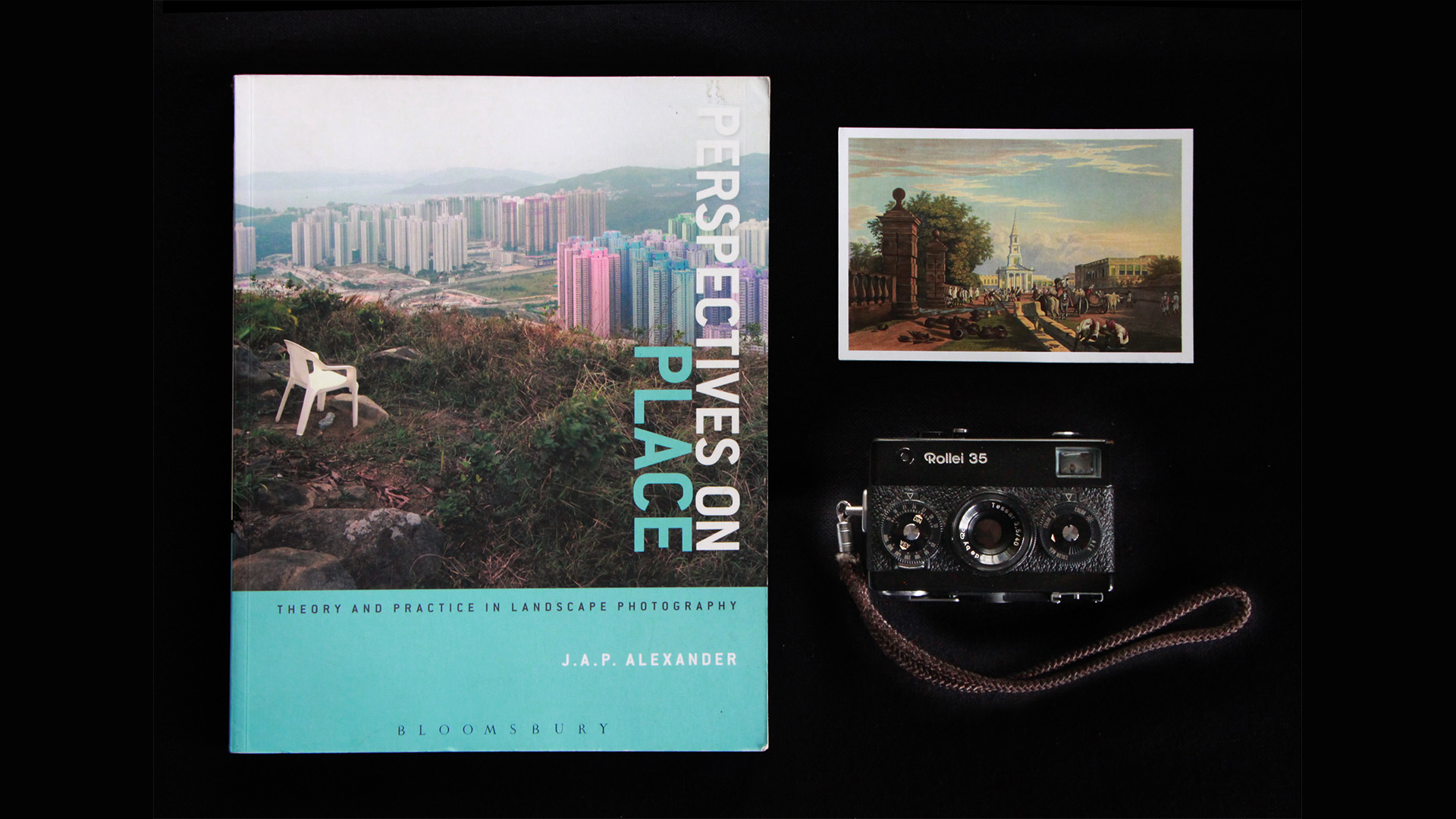

Does “I’m not into landscape photography” strike you as an odd reason to buy a book about landscape photography? Okay, I do look at landscape photographs – you can hardly avoid it, even if you want to – and sometimes I even dabble in it myself. But I used to think that landscape was not one of my favorite genres of photography. Fortunately, I started to question that idea some time ago, and now I have well and truly put the notion to bed. The turning point for me was when I read the book Perspectives on Place: Theory and Practice in Landscape Photography by JAP Alexander.

“I don’t do landscapes” and Other Misguided Notions

My main limitation, I believe, was a narrow understanding of what landscape photography is or what it can be. I mostly thought of it as… well, Mark Knopfler said it better than I can: “The drawing room tea-set / Wants horses, sunsets / Sweet nothings – the seaside with yachts.”

I don’t claim any kind of moral high ground; I’ve taken my fair share of “sweet nothings” – pleasant but unoriginal photos of horses, sunsets and the rest. Sometimes the sky turns a certain shade of pink, a flock of birds takes flight and you gotta do what you gotta do. But I’m not just talking about landscape photography by dilettantes such as myself.

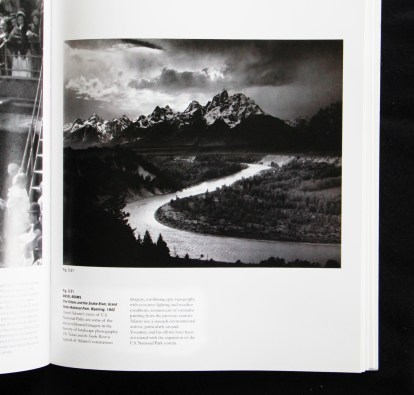

In 2012, I went to see an Ansel Adams exhibition at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. I was blown away by his compositions, dramatic timing and mastery over light and shade. But the exhibition did not move me, or make me think, as much as some others have – World Press Photo exhibitions, for example. Now clearly, this is just about my own preferences, and not a general slant against photographs that celebrate picturesque or sublime vistas. But it took me a while to discover the other forms of landscape photography are out there. Wanting to broaden my vistas (literally) was one reason for purchasing Perspectives on Place.

Perspectives on Place Overview

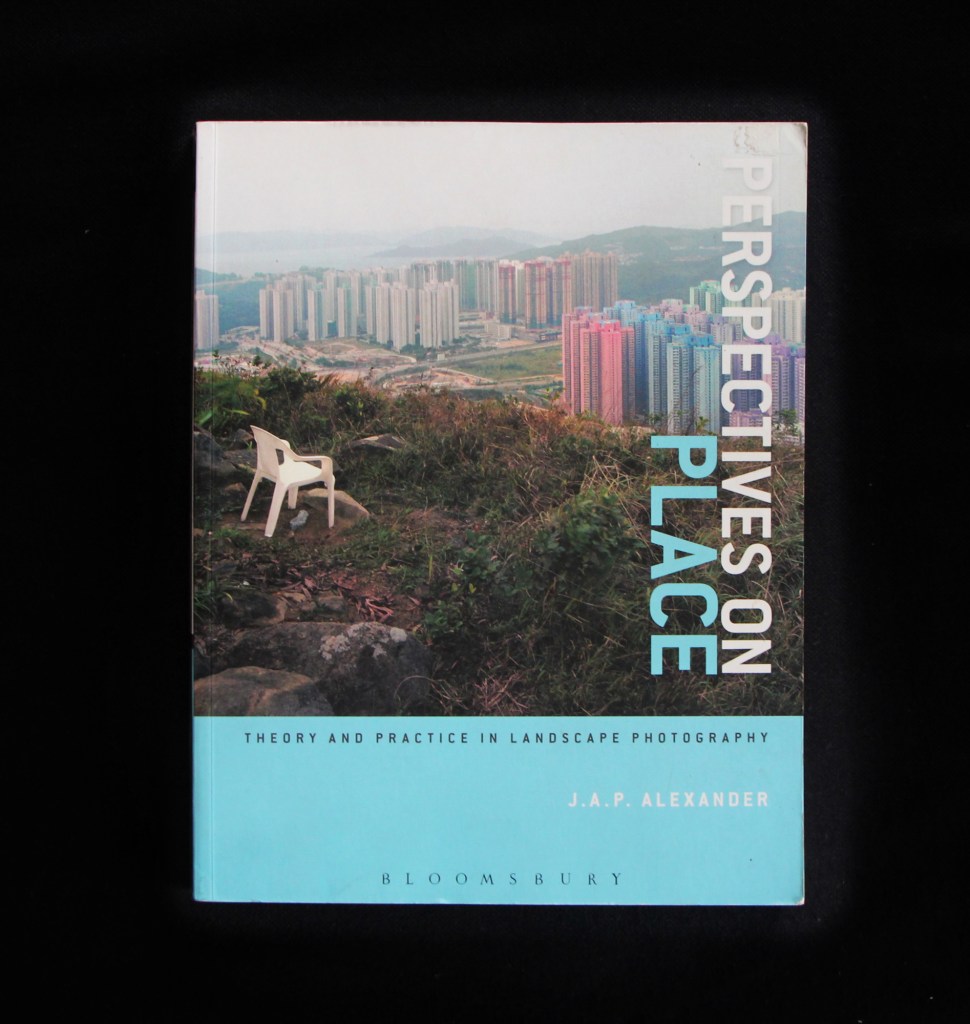

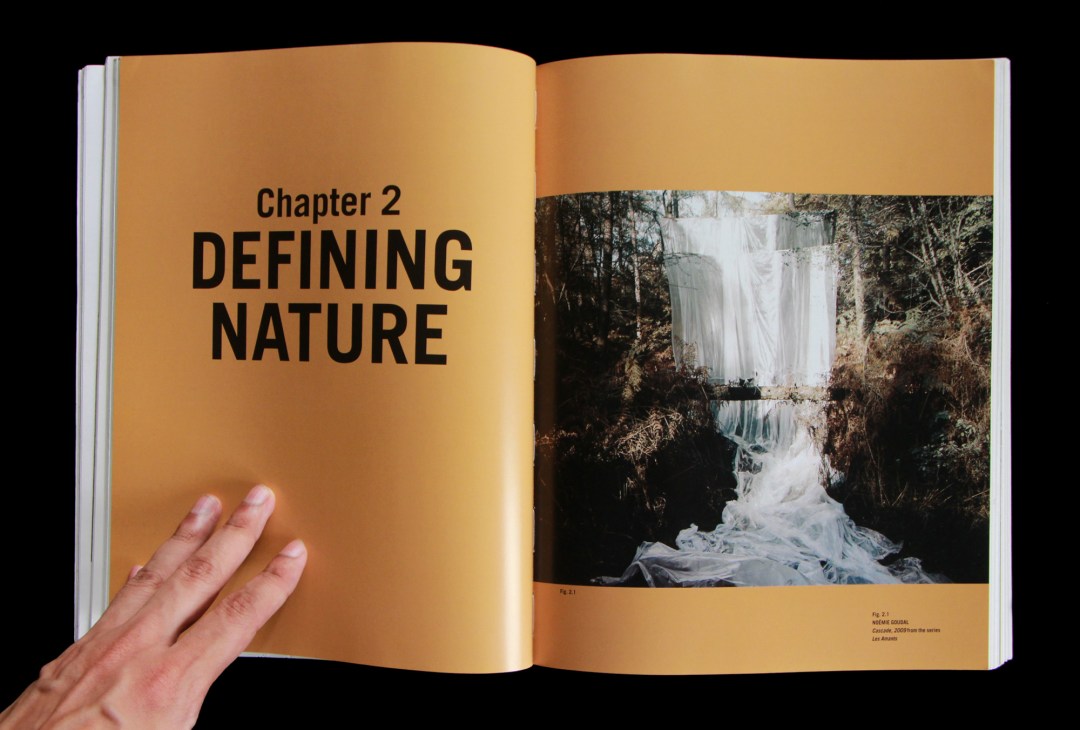

Perspectives on Place is written by JAP Alexander, a freelance photographer and writer. It features images by a number of photographers who have engaged with the landscape in diverse ways – from stalwarts of the past like Ansel Adams and Fay Godwin, to contemporary and postmodern work by artists such as Noémie Goudal and Tonk. Even Spirit, the NASA Mars rover, gets an entry.

The cover image – Hong Kong, Back Door 02 by Michael Wolf – sets the tone for what is to come. I’ve seen many photos of the Hong Kong skyline taken from the surrounding hills; in fact, I took one such photo myself when I was there in 2011. In Wolf’s place, many of us would have instinctively framed to exclude the plastic chair, but its inclusion makes it so much more surprising and thought-provoking. Who was sitting there, and why? What went through their mind? How much of the landscape – and philosophically speaking, how much of life – do we miss, when we fixate on the grand vista in the distance and ignore the seemingly mundane details closer at hand?

The binding, paper quality, print and layout are all excellent. I photographed some of the pages for this review, but they don’t really do it justice.

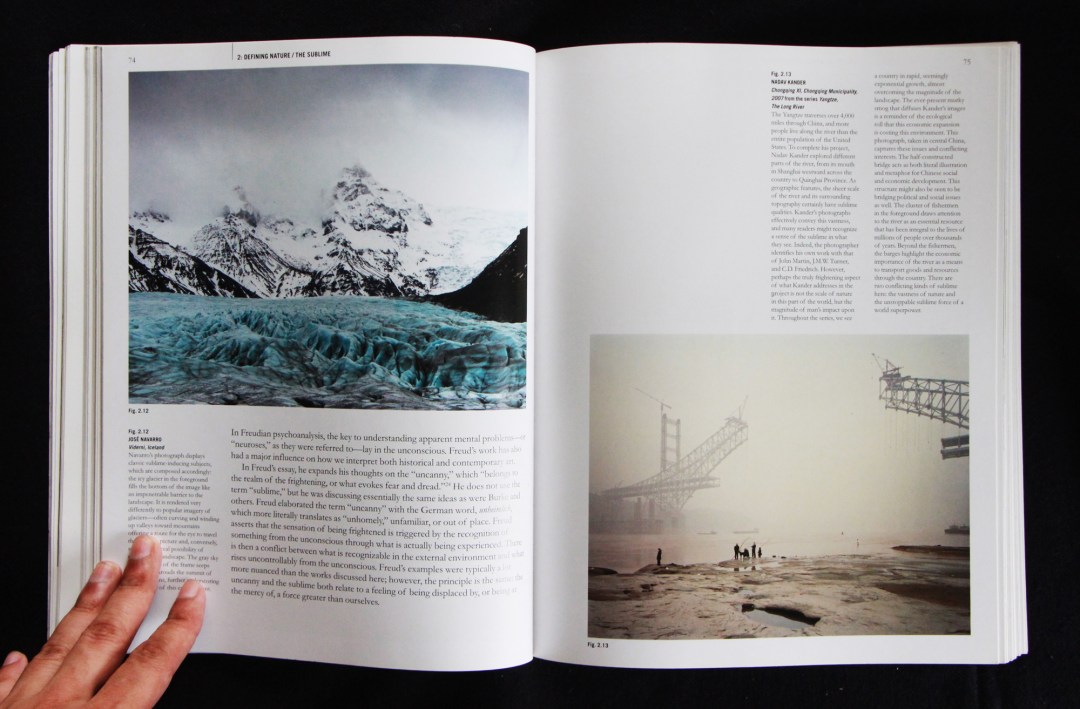

The images featured in the book include remote landscapes like glaciers (Jose Navarro) and national parks (Ansel Adams), but also shopping malls (Dan Holdsworth), unassuming Welsh villages (Keith Arnatt) and even computer-generated terrain (Joan Fontcuberta). Indeed, one of the key messages of the book – as Paul Hill says in the foreword – is that “you don’t have to go to remote or exotic places … to make landscape photographs. The land is … everywhere – in your backyard and garden, in retail parks and industrial estates, as well as in picturesque dingles and glens” (p6).

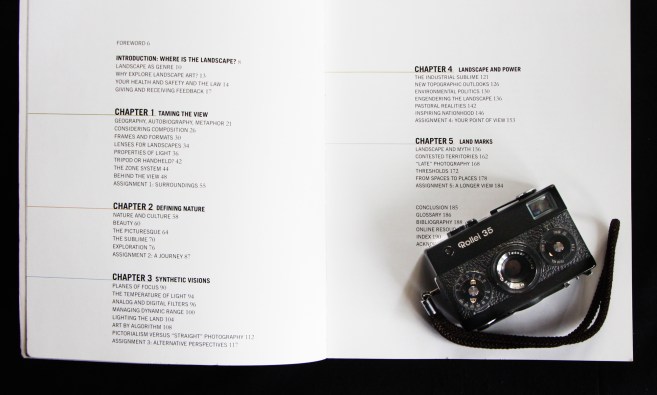

The book is designed as a “primer” (p13) – not just for “makers of landscape pictures” but for anyone who is interested in contemporary landscape photography. It has five chapters addressing broad conceptual themes such as Defining Nature (chapter 2) and Landscape and Power (chapter 4). At the end of each chapter, there are end notes indicating sources and further readings, ideas for projects and questions for research and discussion. As a casual reader I didn’t do the assignments myself, but I can see how they would add value, especially if the book is used as part of a (formal or informal) photography curriculum.

Technical Aspects

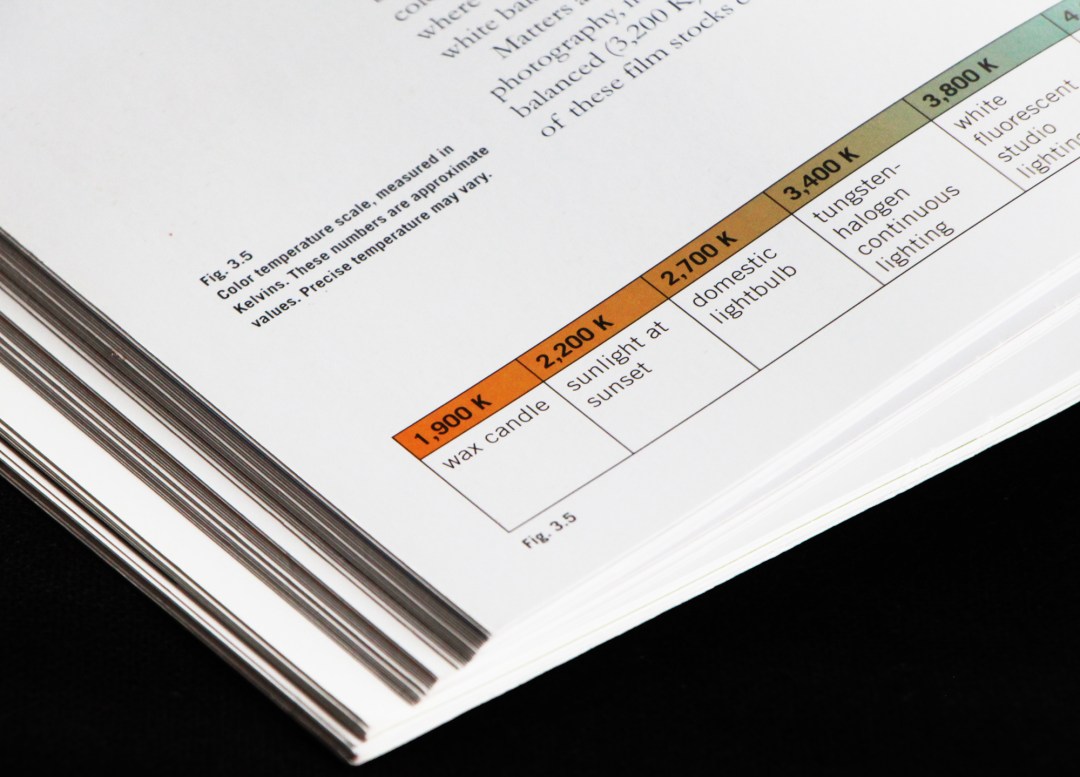

The book covers both technical topics – such as composition, lenses, filters, color temperature and the Zone System – as well as theoretical and philosophical aspects. The former, I found, is a bit general, and not detailed enough to be truly useful. But I can overlook that because there are many other “how-to books” for landscape photography on the market, which cover such topics more thoroughly.

In any case, I think such books can only take us so far. As someone with no formal education in photography, I found that after the first couple of years, once I’d got my head around basic technique of exposure triangle, focal lengths, and so on, my learning curve hit a plateau. It took me a while to figure out what I needed to make further progress: engaging with the work of other photographers, learning more about history and critical theory, and reflecting on the “why” rather than the “how.” For me, Perspectives on Place delivers most solidly in these areas.

Even in the technical sections, it offers at least three things which most “how-to books” don’t. First, it avoids the trap of being too prescriptive – a refreshing change from books which try to brainwash beginners into following certain “rules.” For instance, after briefly introducing the rule of thirds, Alexander warns us that ‘adhering to such a formulaic approach for one’s own picture making is not conducive to a progressive approach’ (p27).

Second, the technical sections are illustrated not with generic images as in many other books, but with work by outstanding past and contemporary practitioners. Cartier-Bresson’s The Hauts-de-Seine ‘department’ illustrates the section on composition, and Fay Godwin’s Fence, Parkend Woods features in the section on formats and aspect ratios (unusually for a landscape photographer, Godwin used a 6×6 camera for much of her work).

Third, discussions of technique are interwoven with critical theory and aesthetics. Alexander says in the introduction that technique and theory are not really separable, and that this book “is designed to deliberately blur those false boundaries” (p13). The section on view-camera movements and tilt-shift lenses, for example, analyses Richard Page’s use of a skewed focal plane to suggest misinformation and uncertainty.

Landscape Theory and Philosophy

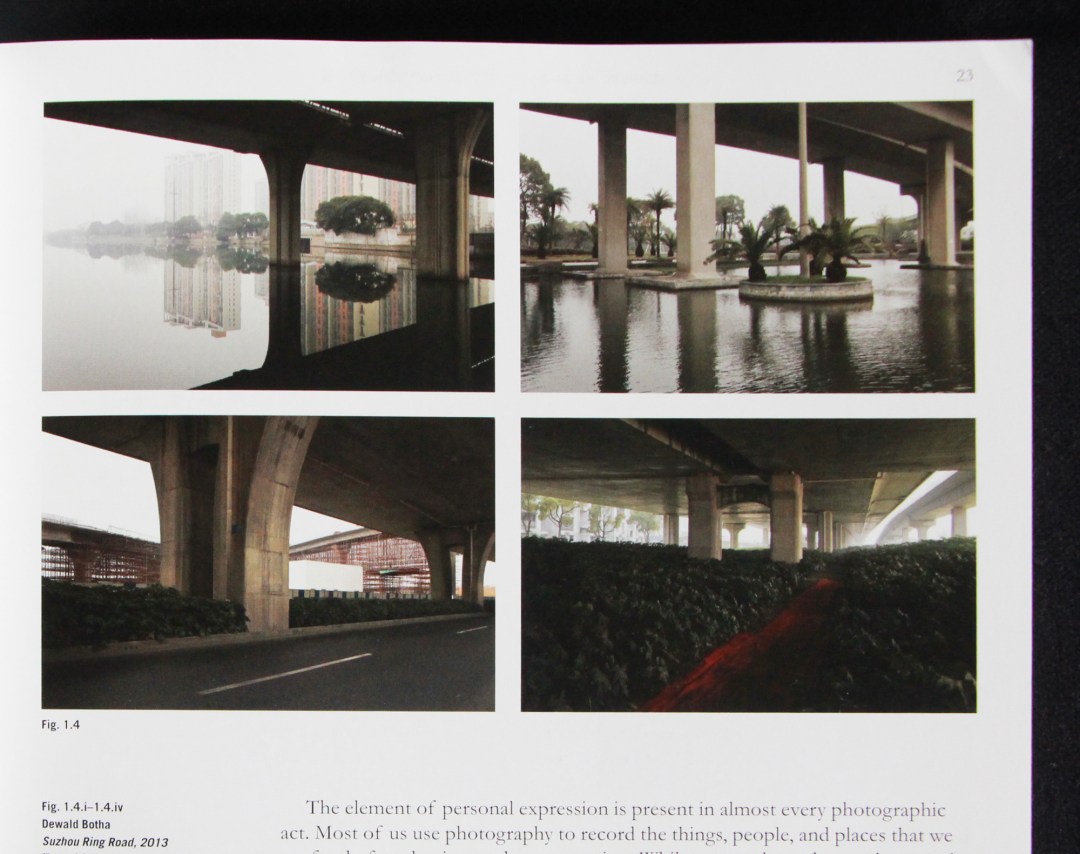

The theoretical discussions, illustrated with some excellent photographs and insightful captions, are truly eye-opening. Take for example Robert Adams’ assertion that landscape pictures can offer us “three varieties – geography, autobiography, and metaphor”. The quote, as it stands, is rather abstract, but Alexander brings it to life through an illuminating discussion and a series of examples, one of which is Dewald Botha’s Ring Road project. At a basic level, Botha’s photographs are a geographical record of a transport system in the city of Suzhou. But the ring road can also be seen a metaphor for an enclosure or defensive wall. Finally, for Botha, the metaphor also carries autobiographical connotations – linguistic and cultural barriers that can isolate the outsider.

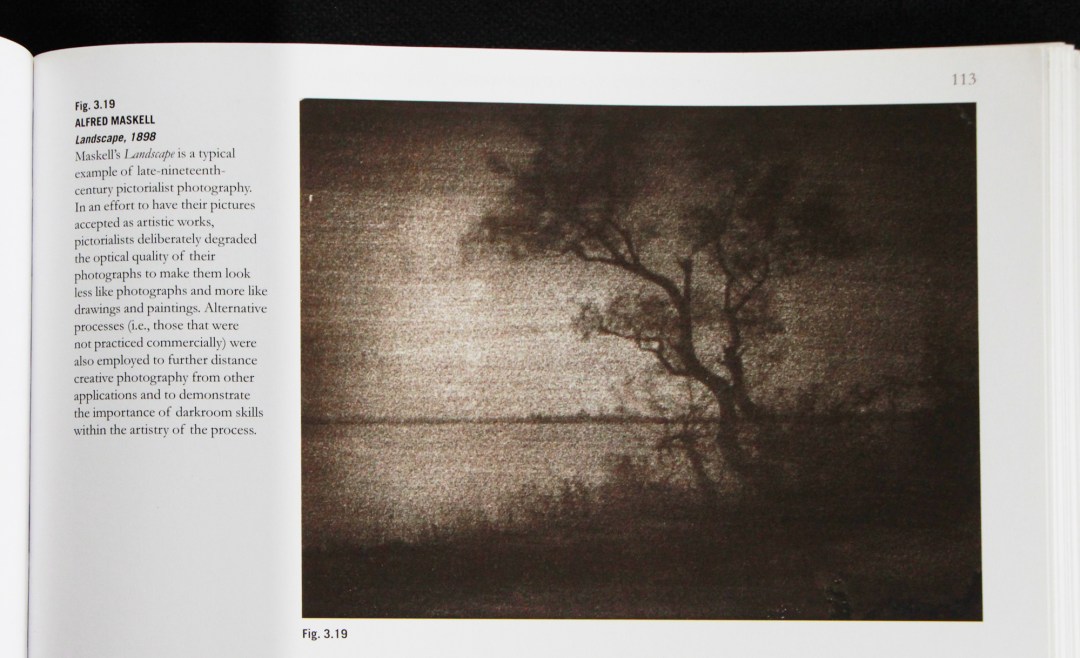

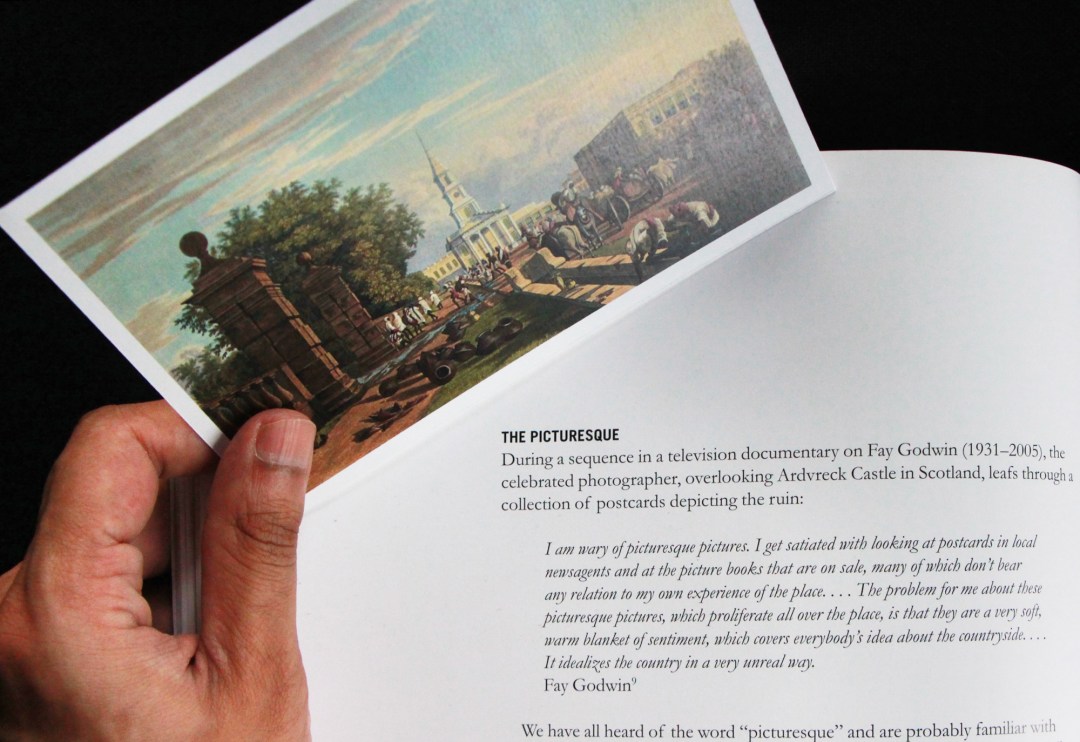

The book also covers movements and trends in landscape photography including pictorialism, Group f/64 and the New Topographics school, as well as aesthetic issues such as “picturesque” and “sublime” depictions of landscape in painting and photography.

Among others, I enjoyed the discussion on WJT Mitchell’s theory that landscape is more usefully understood not as a noun but as a verb (as in, “to landscape”) – for example through cultivation, industrial development and other human interventions. More subtly, as Alexander says, framing and composing a photograph is also an act of “landscaping” – creating, reinforcing and sometimes subverting expectations of how the land should look.

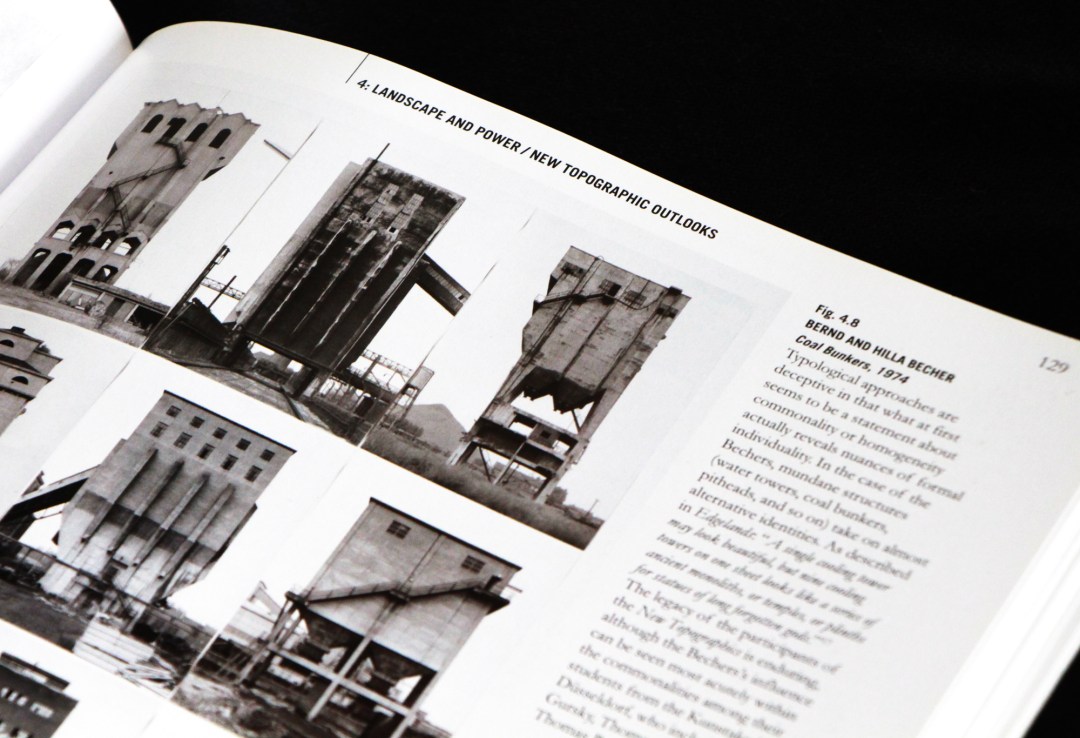

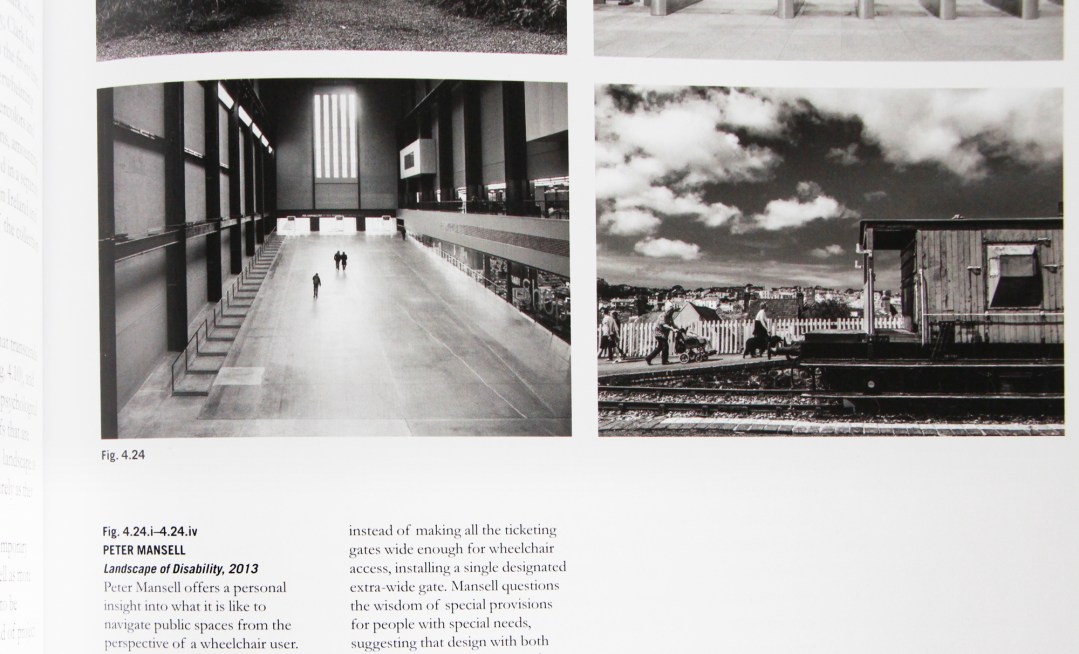

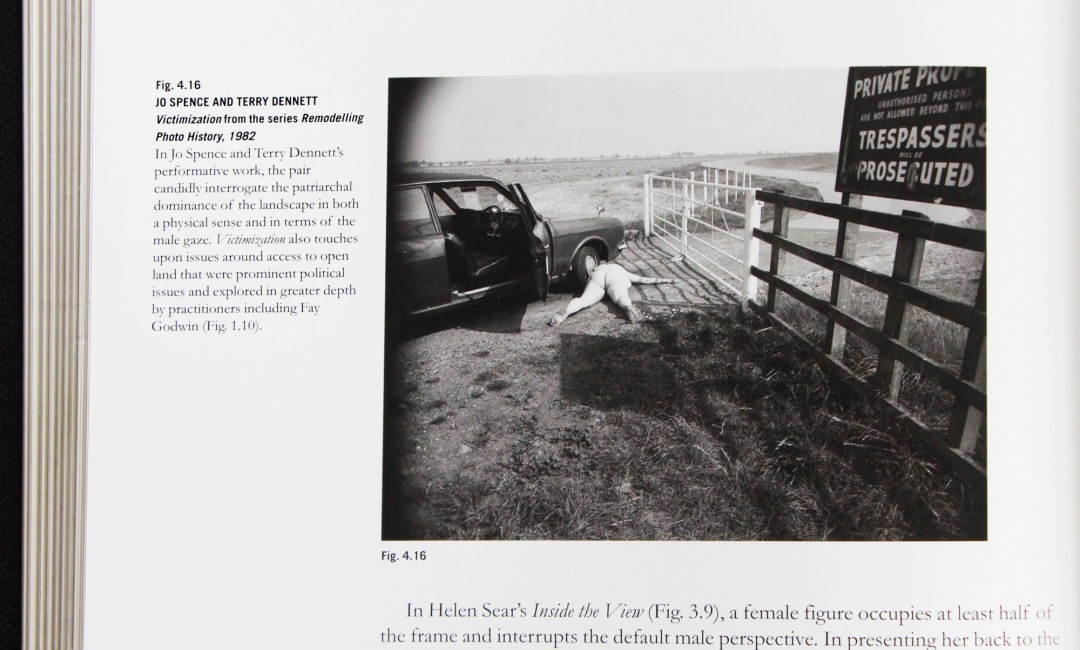

Chapter 4 (Landscape and Power) is particularly concerned with such big questions. Some sections focus more on aesthetics, such as the “industrial sublime,” deadpan aesthetics, urban exploration and the allure of decay. Others address political issues like land ownership and access, environment and conservation, gender, national identity and minority perspectives.

Final thoughts

I won’t attempt to summarize or even list all the themes covered in this extraordinarily wide-ranging and thought-provoking book. Suffice to say, Perspectives on Place is ambitious in its scope, but strikes a really good balance between breadth and depth. Likewise, the theoretical discussions are comprehensive, but I did not find them difficult or dry. The photographs are well-chosen, and the captions really added to my understanding and appreciation. If I have a criticism, it is that the roster of photographers – mostly male, nearly all from Western Europe and North America – is unfortunately not as diverse as the range of landscapes and approaches represented in the book.

If you’re interested in the theoretical aspects of landscape photography, I believe Landscape: Theory (1980) edited by Carol Di Grappa is another excellent book. Unfortunately, I haven’t read it myself; it’s out of print and quite expensive (anyone want to lend me a copy?) Bloomsbury, publishers of Perspectives on Place, also have a sister volume on portraits: Train Your Gaze: A Practical and Theoretical Introduction to Portrait Photography by Roswell Angier. I’m currently reading this book, but so far (only a couple of chapters in), I find it less engaging than Perspectives on Place.

This is my first book review for Casual Photophile; my contributions so far have mostly consisted of gear reviews. And when reviewing gear, one of the best things I can say about it is that it makes me want to go out and take pictures. Perspectives on Place is the equivalent in book form. Turns out, I am into landscapes after all.

Buy the book here

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Your final thoughts are a bit rich Sroyon. Trying to appeal to the woke crowd are we? Disappointing, son.