Spoiler: Stephen Shore’s American Surfaces is a good photobook. I write this at the very start of this article, because I don’t see much point in treating this as a traditional book review. In cases like these – where the book is already famous and accepted as important – it can either go one of two ways; either I hum and haw about the tired clichés and say “Well, it’s actually not that great” and earn a whole bunch of cool points with the cool kids who say cool contrarian things on the internet for extra clicks, or I can gush and fawn over the luscious colors and vibrant views of vivid life in every frame. But it’s obviously a good photobook. It has been reprinted multiple times and is cited often as a key text for anyone studying the popularization of color photography as an artistic practice. It’s a good book – great even! The reason I find myself writing about this very good book today is because it seems uniquely relevant to the world we are living in now.

The thing about photography is that it is impossible to tell which aspects of life today will be interesting to our future selves. Never has this been more apparent than friends and family sharing images of their pre-Covid lifestyles on social media during the ongoing pandemic; a world of hugs and concert crowds and restaurant plates, scenes of close embrace and bustling streets, trips abroad and foreign friends. Throwaway snapshots have taken on a new importance after a global shift which has brought varying degrees of isolation to every one of us for over a year. This incredible ability of photography to elevate the ordinary to something more keeps us invested, keeps us clicking away at that shutter button even on days when it seems like there isn’t much worth photographing at all. For many reasons, photography for the sake of photography is often a good enough reason to take pictures.

This very site’s founder and editor, James Tocchio, was recently asked during an Instagram Q&A to show his favorite photograph of all time. I wasn’t surprised when I saw that his answer was a photo showing his children. I think most people, even the most die-hard of art-nerds, would give a similar answer. There are certainly cooler answers to give, but giving the boring answer – my family, my loved one, a photo that represents happiness rather than cool-ness – is so vital when posed with these questions because we must never forget that photography at its absolute core fundamentals is simply a tool to represent a world inside an image.

In an interview with Lynne Tillman in 2004, American photographer Stephen Shore spoke of his seminal work American Surfaces with a simple line; “I was simply recording my life.” Nothing particularly interesting happens in this book, and that’s kind of the point. Shore captured the ordinary, and every type of ordinary he could find. It was the ordinary of his own life. It was sign posts and shopfronts, airplane meals and fine dining, scruffy party-goers and well-dressed elders. It was in this very variety, this lack of clear subject, in which the ordinariness of everyday life in America at that time shines through today.

For 22 months beginning in March 1972, Shore traveled across the continental United States with a simple Rollei 35 – a camera so diminutive in stature that it earned the title of smallest 35mm camera in production at the time [more on the Rollei 35 can be seen here in our review]. It was this tiny camera which allowed him to blend in, to never give the air of a serious photographer, and which granted him accessibility to people and places without question or query. It was the normality, the civilian nature of a compact 35mm loaded with color film which let him make important work right under the noses of people looking for Leica-clad members of Magnum.

Shore cites Walker Evans’ 1938 book American Photographs as having a strong influence on how he would begin to view the world through the eye of photography. Evans’ book championed the idea that the photographer and the photograph cannot be separated from one another, and this idea of the eternal battle between objectivity and subjectivity is something which Shore leaned into heavily in his early years.

A Rollei 35 SE, similar to the model used by Shore.

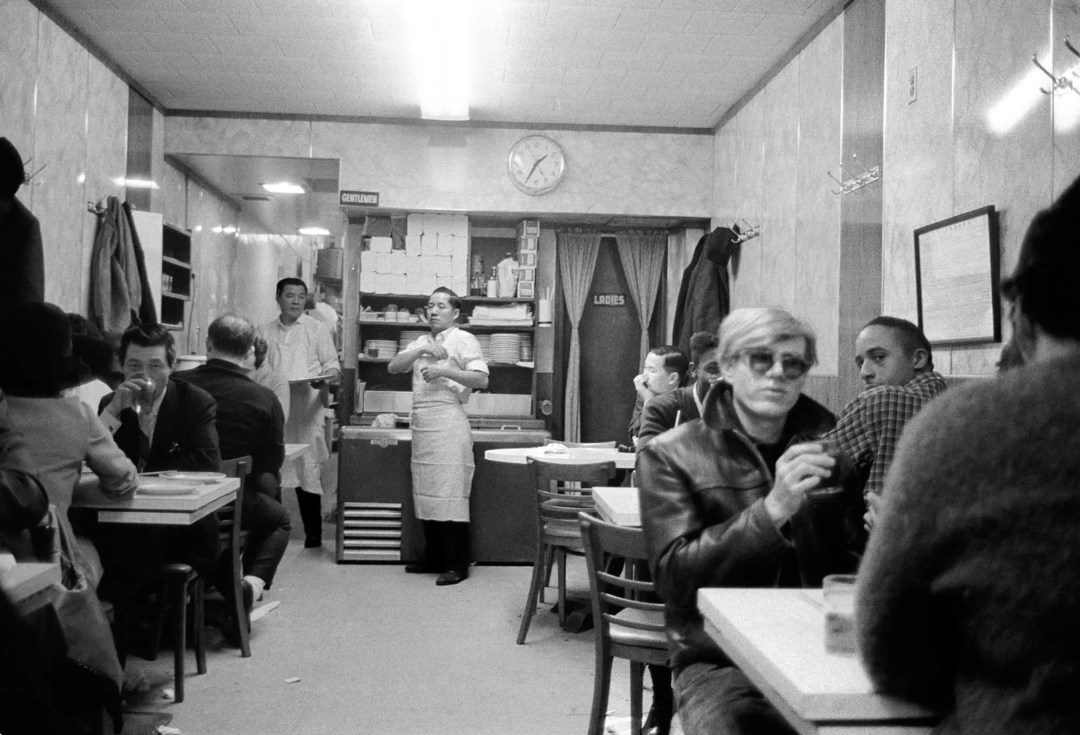

But there was a much stronger, and perhaps more culturally famous influence for the young artist. As a teen, Shore grew and formed a working relationship with Andy Warhol after meeting him at a movie showing at the Filmmakers Cinematech in New York. A short film of Shore’s was playing before Warhol’s piece The Life of Juanita Castro (1965). Shore asked could he visit The Factory in the hope of photographing the people who inhabit the space. Uncharacteristically, Warhol obliged and Shore created several environmental portraits of key figures of the era such as Edie Sedgwick and Lou Reed. One particular photograph shows Warhol and company in a Chinatown restaurant in the early hours of the morning. Warhol appears not even as the focal point of the dream like picture, instead sitting off to one side, oblivious to his own grandeur within the everyday setting. Shore’s wide angle of the restaurant depicts kitchen staff and other patrons going about their business with Warhol perched in the bottom right half of the frame casually raising a glass to his mouth and acknowledging the camera.

Shore learned a lot of his art sensibilities from his time at The Factory. At just seventeen, it would be difficult not to have had such an experience play a part in shaping the future of Stephen Shore: The Artist. What was gained from this time was an understanding of the importance of ephemera and how it relates to experiential art forms but more importantly, it focused Shore’s attention on the everyday. Warhol was an esteemed artist who was noted as championing the everyday as core subject matter for his art. The Pop Art movement was in fact, art for the people, art that utilized a language the common man could understand. We see this in perhaps his most famous work, Campbell’s Soup Cans (1962). This exploration of the ordinariness of food packaging was an obvious commentary on the banality and beauty of living.

From here, it’s going to feel like I’m skipping forward for a moment. The American Surfaces series was shot between 1972 and 1973, but it wasn’t published as a proper book until 1999 – nearly three decades later! Before this, it existed merely as a gallery exhibition. Shore was just 24 years old at the time he took these images, yet served another full lifetime in this respect when the book was eventually published at age 51. At the time that this series became a book, his life – and his career for that matter – were very different.

In 1982 – nearly a decade after American Surfaces – Shore published his breakthrough series Uncommon Places. To many, this was the work which put Shore on the map. To many, this was his first major work. The structure was much the same as before; Shore set off on a road-trip across America with a camera. Only this time, the pocket-sized Rollei 35 was replaced with large-format view cameras. The effect on his workflow was immediate.

The compositions became sordid affairs, full of strict attention to detail and precise calibration. The resulting pictures were stark and true, with an emphasis on the hyper-real beauty of interesting scenes in otherwise normal locations. These images are cinematic in nature, bearing uncanny resemblance to even recent films such as The Coen Brothers’ No Country For Old Men. But it is only when contrasted against this later work does Shore’s early American Surfaces begin to make sense from an intentional and artistic perspective.

“There was a time though that something else changed. When you put an 8×10 camera on a tripod, the decisions a photographer makes become very clear and conscious. There is a period of awareness, of self-consciousness, of decisions […] I felt like I could take a picture that really felt “natural,” or that you were less aware of the mediation, that was harder to achieve when I started using the view camera because of the self-consciousness of the decisions. Over time, I very slowly examined each of the decisions involved in putting a picture together, and played with it, and tried to learn how to do it so that I could eventually get to the point of very consciously taking a picture that had much of the same quality that American Surfaces had, except doing it with this great big camera.”

That was Shore speaking to Gil Blank in 2007. And this is him speaking to his publisher, Phaidon, in a promotional interview five years later:

“I felt that the decisions I was making as a photographer were so influenced by my conditioning that if I removed myself in certain ways from the decision-making process I would arrive at a less mediated experience. And I think to some extent it’s true. […] I felt that I ought to be able to understand an image in a certain way, understand the visual, artistic conditioning that I’m imposing on the image and eliminate it as much as possible from the picture. […] I’m taking a screenshot of my field of vision at various moments, not necessarily when I was taking pictures, and see what it’s like to look, to stand back from seeing and really observe what I’m looking at and how I’m looking at it.”

As much as Shore wanted to continue his methodology and process from American Surfaces to Uncommon Places, somewhere not too long into the second Great American Road-trip, he discovered it wasn’t possible. The more involved that the photographic process became, the less it became about capturing everyday life. An idea could pass before it could be photographed. Instead of representing the original moment of interest, the photograph would now show the moment after a photographer had noticed something of interest, unpacked their camera, set-up their tripod, framed and composed the shot, and then took the photo. Those are two different moments.

In both respects, American Surfaces and Uncommon Places are as much about the practice of photography than any subject that appears within their frames. In fact, to many who view the books in isolation of a wider knowledge of Shore’s work, they may even describe the images as boring or mundane (such is everyday life).

From American Surfaces

In American Surfaces, there is a sense of immediacy. Shots are often not framed well – a screenshot of his field of vision as Shore would say – and they also contain fragments of the presence of the camera itself. The Rollei 35 had a maximum aperture of f/3.5 which meant it could not shoot very well in low light. Coupled with the usage of low-ISO Kodak slide film, this meant that Shore needed a flash for the majority of his exposures. However, because the Rollei 35 was a compact camera optimized for pocket-ability above all else, it meant that the flash mount had to be located on the camera’s bottom rather than the top. The presence of flash in any form can alert a viewer to the camera’s effect on an image, but anything below the camera creates unusually large shadows which loom over people and objects in many frames. The pictures are sharp. They are undeniably vibrant. But they are undoubtedly photographs. At no point, do these images ever feel like screenshots of Shore’s field of vision. When viewing this series, I am always aware that what I am looking at are photographs produced with a camera. It imposes its presence on the scene as much as the photographer himself.

From American Surfaces

From Uncommon Places

And so flipping to Uncommon Places whose images are so lucid that it feels as though I could step inside and walk around, I am hardly aware of the camera at all. But for this to be possible, it meant that there was a trade-off and that barrier to realism posed by the ever-present flash in American Surfaces was replaced with Shore’s own sacrifice of a moment for our own enjoyment of its image.

Again, from the interview with Blank in 2007:

“I couldn’t do some of the pictures I was doing for American Surfaces as easily, like pictures of food. I did my pancake picture the next year, the first year with the 4×5. But to do it, I had to be standing on a chair, looking into the camera, and by the time I did it, the food was cold because it’s a big production, and I have to get permission from the restaurant, because if I had this camera and this tripod and I’m standing on one of their chairs, it’s not as simple as just looking down at the plate in front of me and snapping a picture of it.”

From American Surfaces

From Uncommon Places

With Shore’s work, I don’t find answers to how we can represent the everyday, but rather questions as to what we must give up in order to do so. Photographs that look like photographs will distract from the scene which they aim to represent, and to me, that’s a totally acceptable trade-off. After all, I like photographs. But to others, mainly those whose attraction to photography is its ability to capture reality, the compromise of life by the artist in order to achieve pictures of sublime realism may detract from that very realism which they aimed to preserve – much like a documentary film where the presence of a film crew causes the subjects to act differently.

I believe Uncommon Places to be about photography showing the beauty of everyday life, while American Surfaces displays the beauty of photography itself by reflecting itself within banal scenes of normality. There is place for both frames of mind, and I actually believe an understanding of the trade-offs between these two reference points is vital for any photographer today.

Over the years, far more photographers have been drawn to the Uncommon Places pictures than any other made by Shore. This is, after all, the series which cemented his place as an early pioneer of color work in the critical art space. It is a large book filled with crisp images of immense detail. It is the kind of work every photographer vies to make in their lifetime. But American Surfaces is the book I revisit more than any other. It’s the book I wrote my college thesis about nearly a decade ago. To me, American Surfaces is a collection of images taken by a man living out his life. The more meditative Uncommon Places is too pre-occupied with composition to eat the damn pancake.

Of course, I am not naïve. I understand that the goal of all photography is not to simply capture moments of reality. There are a wide variety of disciplines which can contain image-making that go in every direction imaginable. But as a person who enjoys the pursuit of realism with aesthetic flair, I have always had a penchant for Shore’s work. I simply wonder if when looking back upon his life, Shore ponders what his favorite photograph may be. I wonder if, like our editor James, his choice favors an imperfect representation of a great moment, or a perfect depiction of something missed.

Shop for American Surfaces and Uncommon Places

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Whaouuu 😉 well done ! Great !

Thank you so much. Very very good.