As is often the case here at Casual Photophile, today’s article was born from a conversation amongst the writing team. In our series of Desert Island articles, we write about the single camera or lens or film we’d choose from different brands or countries or formats if we could only pick one. It’s a fun exercise, and each article results in a sort of All Star Team of gear. But what would we pick if we weren’t limited by brand or country or format, etc.? Which one camera would we buy with endless money, throwing practicality aside? That’s the question answered by today’s article.

Give a look to the amazing machines which are our writers’ Holy Grail cameras. And let us know yours in the comments below. Enjoy.

James – Zeiss Ikon Hologon Ultrawide

I’ve mentioned the Zeiss Ikon Hologon Ultrawide to lots of photo geeks in casual conversation over the past five years. Just one of them has known what I’m talking about. Most people think I’m talking about the Zeiss Hologon 16mm lens for the Contax G series cameras, or an old (and rare) Zeiss 15mm Leica M mount lens. But I’m not talking about a lens. The original Hologon lens was fixed to a Hologon camera. My Holy Grail camera, in fact.

The Zeiss Ikon Hologon Ultrawide was first produced in 1969. A mechanical 35mm film camera, it was fitted with the lens from which it derives its name, a Zeiss Hologon 15mm F/8 (fixed aperture, fixed focus). This lens provides a 110º field of view. The camera has a viewfinder, a bubble level, a pistol grip accessory, a graduated neutral density filter to kill vignetting, a tripod socket, thumb-powered film advance, and a shutter with speeds from 1/500th of a second down to Bulb and T.

It is essentially a finely made metal clockwork camera with an enormously wide lens. Okay, 15mm by 2020 standards isn’t too wild. But back when this camera was made, 15mm was pretty wild. So wild, in fact, that Zeiss Ikon, the company who made it, barely sold any units. Despite making great cameras, Zeiss Ikon folded in the 1970s, after which their parent company Carl Zeiss took over. For the next few years, Carl Zeiss would produce small batches of Hologon cameras per year. In addition, they converted a number of the 15mm Hologon lenses to M mount (less than 1,000 units). Decades later in 1996, the famed Hologon was recomputed and reborn in Contax G mount, becoming a legendary lens in its own right.

The Zeiss Ikon Hologon Ultrawide was and remains an expensive camera. When new, it retailed for $825. That’s more than $5,500 in today’s money. And $5,500 is just about what a nice, fully functional example will cost today. The high price alone puts the Hologon fairly out of reach for most buyers. And then its rarity makes it hard to find even if one has the money (there are a handful of imperfect ones on eBay, usually, but who wants to spend $3,500 on a camera with a hazy lens?).

But beyond the high cost, what really makes the Zeiss Ikon Hologon Ultrawide a Holy Grail camera is that it’s just so impractical. A fixed 15mm lens that can’t focus or change aperture on a camera that costs five grand? How does one possibly justify that? I guess if one owns a camera shop and a camera blog whereby the entirety of the business operations consists of buying and selling cameras, and writing articles about special cameras for other photo geeks to enjoy, one might be able to justify the purchase. It is, after all, a business expense. Yes… Yes.

What say you, dear reader? Should I buy a Hologon?

Jeb – Hasselblad XPan II

Call me a sucker for weird formats; Polaroids, square 120, and even 110. I love shooting them all because they offer unique compositional challenges. Technically the Hasselblad XPan is a 35mm camera and you can use it to shoot 24x36mm negatives. But the whole point of the camera is the switch that allows it to shoot panoramic 24x72mm negatives. Panorama photography is a small niche in the field, but wide composition is something that has long appealed to me and is not a little influenced by films like The Master and Kenneth Branaugh’s Hamlet.

There are a few options for panorama cameras, but none reach the quality of the XPan. Designed by Hasselblad and produced by Fuji, who released it in Japan as the [arguably prettier] TX-1, it was released in 1998 along with three new manual-focus lenses (30mm, 45mm and 90mm) specially built for the camera. It had automatic exposure, a silent shutter, exposure compensation and a motor drive. The XPan 2 was released in 2003 with modest improvements, such as an expanded bulb mode allowing for exposures up to nine minutes long, a self timer, and in-viewfinder exposure information. One cool function is that the film is completely unwound and then rewound frame-by-frame each time a photo is taken so that each exposure is protected as it’s taken, and so that the format can be changed mid roll.

But what you really want with the XPan is that wide negative. It gives photographers a cinematic perspective on whatever subject they choose, and while many people consider the XPan limited in its practicality, I say the only limitation is the photographer. Unfortunately the niche-ness of, and high-demand for, the XPan has seen prices skyrocket – well beyond the reach of most of us, including myself. XPans regularly cost a minimum of $3,500, and that’s with only one of the three lenses. If I were to take the time to average the price of the eleven XPan II’s currently listed on eBay (which I did), I’d find that the average the average price of an XPan II on eBay is an astonishing $5,886.

Still, if there’s one camera out there that I’ve never used but still salivate over, it’s the XPan. At the very least it would save me time cropping to my favorite aspect ratio.

Connor – Zeiss Ikon ZM

Being abandoned with nothing but one camera would be difficult for me regardless of my fictional budget. I’m just as much a collector as I am a photographer, and using/learning to handle different cameras is just part of the fun to me. That being said, I think I would go with the Zeiss Ikon ZM 35mm rangefinder. With a suite of Zeiss lenses, of course.

I prefer rangefinders for my style of shooting, and the ZM’s utilitarian feature set and access to some amazing lenses make it hard to ignore. With a shutter that’s just one step faster than the comparable Leica M7, and a metering system that’s very similar as well, aside from aperture priority, it’s clear who Zeiss had in their crosshairs when designing the ZM. It’s lighter, faster, and, at least in theory, more accurate to focus than the Leica due to its longer rangefinder base.

I can’t write any more about the ZM without talking about the lenses that come with it. The M Mount Zeiss lenses come with a powerful and deserved reputation (check out this review by Dustin to see for yourself) as the cream of the crop in terms of optical sharpness and design. I know the M mount has a huge variety of lenses and manufacturers, but there’s something about putting a non-Zeiss lens on a Zeiss body that feels… unholy. I’d rather have Planars and Distagons and Biogons on my Zeiss camera than Summicrons or Skopars. I will fully accept my contrarian badge and wear it with pride, as long as my desert island has enough batteries to keep the ZM working forever.

Cory – Nikon F2 Titan

I’ve had far too many cameras pass through my fingers since I tumbled into the rabbit hole of film photography. Some of them have been average and forgettable, others surrounded by hype and storied reputations. At a certain point you realize that gear doesn’t really matter all that much. Some features are useful or even necessary to be sure, but at the end of the day it all comes down to what camera speaks to you on a deeper, emotional level. Which one begs to be used? To be passed down to your kids or grandkids? Which camera is as much of an heirloom as it is a trusted companion to your life?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot lately. James went through this same journey when he decided to purchase his Nikon SP 2005 Special Edition. Like him, I wanted something fully mechanical, rare, and beautiful. Preferring SLR to rangefinder and already possessing a decent collection of F-mount glass led me to my own personal grail – the Nikon F2 Titan.

The traditional Nikon F2 is a standout camera in its own right, being hand-assembled from over 1500 individual parts. Its all mechanical body capable of continuously varying shutters speeds from 1/125-1/2000th of a second is a marvel of mechanical engineering.

The F2 Titan is ostensibly a standard F2 wrapped in a titanium shell, but its history and rarity are what make it truly special. In 1977 the famous Japanese adventurer, Naomi Uemura asked Nikon to make him a camera that could survive his solo dog sled trip to the North Pole. Nikon created a titanium bodied F2 using special lubricants intended to function at -50c, and tested the camera’s durability by hurling it down flights of stairs in the factory. Nikon produced three F2 Titanium Uemura Special cameras in total (the first Titanium cameras ever made, in fact). Uemura took two of the cameras with him and shot 180 rolls of film during his six month journey.

In 1978 Nikon produced and marketed an extremely small number of bare-metal titanium F2’s. Professionals complained the titanium finish was too reflective so Nikon painted the future models with a thick, textured black epoxy.

The F2P (P for press), was released in 1978 and distributed to two thousand members of the media that year. The F2P can be identified by a serial number starting with 920xxxx and a plain front plate (it is commonly referred to as a ‘no name’ F2 Titan). In 1979, Nikon released the F2 Titan, which had ‘Titan’ engraved on the front plate and serial numbers started with F2T 79xxxx. It was essentially an F2P that the general public could buy. The final and rarest (only 300 made) titanium F2 was designated the F2H. It sported a non-moving semi-transparent pellicle mirror and a huge MD-100 motor drive and MB-100 battery pack. It achieved a blistering 10 frames per second.

I’ve lusted after one of these special cameras for years, ever since I first learned of their existence. Recently the opportunity presented itself via the friend of a friend for me to purchase an F2P in near-mint condition and it’s on its way to me now. I can’t wait to own, and more importantly, shoot such an important and unique piece of Nikon history. I know that Grails aren’t supposed to be attainable. I’m cheating a little by picking this one. Chalk it up to excitement.

Aidan – Mamiya 7

I currently own and frequently use the Mamiya m645, or as I like to call it “the beast.” It’s beautiful. However, if I had to choose a camera that I would consider my “holy grail,” or a piece of equipment that I want so badly but is so financially out of reach that it can’t be justified, would be a another camera from Mamiya. The Mamiya 7 is my holy grail, desert island camera, dream setup, or whatever we want to call it! I crave its lightweight square-like design that’s able to capture sharp 6x7cm medium format memories.

I surprised myself when I considered a rangefinder to be my holy grail camera; but this specific beauty is too handsome to keep off of the top of my dream list. If I had the Mamiya 7 I feel like I could step up my landscape and street photography tremendously with its versatility for any situation. It’s just unique enough, and it has a concise lineup of lenses that would allow me to be ready for any situation.

The unfortunate $3,000 to $4,000 that this camera costs does not seem justifiable, especially when my significantly heavie, “beast” camera is by my side wherever I go. One day, even if it costs me an arm and a leg, the beautiful, lightweight, medium format Mamiya 7 rangefinder will be mine to create a new lifetime of cliché film shots.

Drew – Rolleiflex Hy6 Mod 2

In the world of autofocus medium format cameras, there are just a handful of players. I’m lucky enough to own the Fujifilm GA645, which is awesome because of how compact it is, and the Pentax 645N, which is a thoroughly modern workhorse. When I think about all of the cameras I don’t own but would like to own and yet probably never will own, one stands out – the Rolleiflex Hy6 Mod 2.

Despite having an appreciation for manual cameras, I’m still a sucker for the adornments and conveniences of modern photography. And on top of that, I really love the fewer shots and larger negatives of 120 film. The various 645 autofocus cameras are good, maybe great, but they’re 6×4.5 and ultimately do not boast the best autofocus or internal metering, which are the hallmarks of modern photographic equipment. The Contax 645 could be my holy grail camera, because I adore Zeiss lenses, but at the end of the day the storied shoddy autofocus and wonky electronics make me hesitant about ever purchasing one.

A far better option is the exorbitantly pricey (for me) Rolleiflex Hy6 Mod 2. This beast is a further development of Rollei’s 6008AF but developed to use Sinar digital backs. The Hy6 has a long history of development with multiple companies involved in its production, only to then become insolvent. It is currently produced by DW-Photo GmbH, a reincarnation of DHW Fototechnik itself a vestige of Rollei/Franke & Heidecke.

In any case, the Hy6 Mod 2 can shoot using 6×4.5 or 6×6 film backs, or medium format digital backs made by Leaf or Sinar (we’re talking sensors in the 50+ MP range). With a waist level finder but blisteringly good AF, you can compose shots organically and never miss focus or have to use a loupe/magnifier. On top of this, the 80mm f/2.8 Schneider-Kreuznach Xenotar, the Hy6’s standard lens, produces stunners. Painterly bokeh and razor-sharp. Luckily, not only are there many Schenider lenses made for the Hy6, the camera also accepts the earlier Rollei 6000 lenses made by Zeiss, Rollei, and Schneider. The cherry on top is that the camera’s three TTL metering modes (center-weighted zone, average zone, and precise spot) work as well as any in-camera meter could, making slide film a breeze to shoot.

Put simply, who wouldn’t want a camera that makes effortless 6×6 images that look gorgeous every single time? For that, all you’ll need is 5,000 – 8,000 USD!

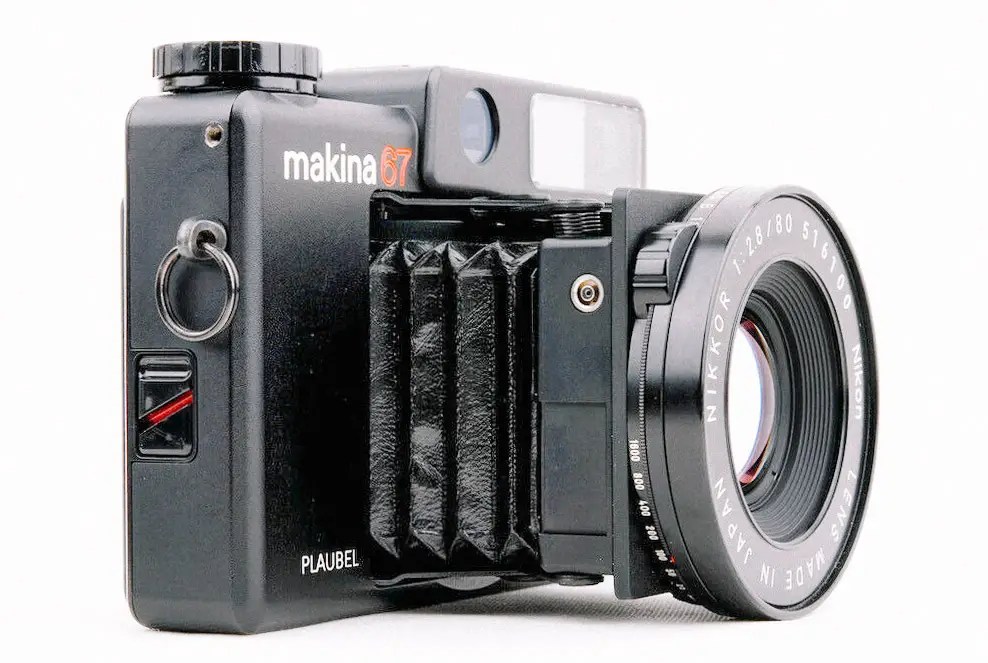

Josh – Plaubel Makina 67

Among photo geeks, I suppose I can count myself rather fortunate. Over the decade-plus that I’ve been shooting film seriously, I’ve finally narrowed my collection down only to things I actually need. I have a pro-spec 35mm SLR system, a classic German rangefinder, an underwater camera, and an antiquated-but-capable TLR if I ever need to shoot medium format. Frankly, not much else outside of that excites me. Luxury point-and-shoots? Don’t care for them. Large format? No time for that. Wacko vintage curiosities masquerading as cameras? No patience. I’ve tried nearly all of these and even geeked out hard over them, but I really don’t think I need any of them. Bummer.

But there is one camera that has piqued my interest for years, yet has completely eluded me – the Plaubel Makina 67. It’s a slick German medium format rangefinder that shoots huge 6×7 negatives out of an incredibly thin body. The compact, bellows-based design is concise and devilishly pretty, a nice contrast to the boat anchors in this category, the Pentax 67 and the Mamiya RB67. The Makina 67 even sports a quick 80mm f/2.8 Nikkor lens, a spec that surpasses the 80mm lenses on the Fujica GM670 and even the legendary Mamiya 7. It seems to solve the weight and size issue I have with most 67 cameras, and does it in style. I might not need it per se, but I’ll be keeping a Makina-sized space on my shelf. You know, just in case.

Some nice cameras in there. Do you have a Grail camera? Let us know what it is in the comments below. Happy hunting.

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Interesting article and camera choices.

The biggest upside to the “demise” of film cameras, for me, has been the opportunity to own and use almost all the cameras I lusted after in my youth.

Almost. There are still a few cameras that I’ve not tried yet. But of those, there really is only one that I’d consider for the criteria you posit.

The Rollei 3003. That camera seems to fulfill all my camera kinks. Odd body style–though informed by the functions Rollei thought were important. A fairly wide system so that I could get pretty camera-geeky about all the various bit and pieces I’d “need” for my own set up. Or, to give in to the temptation to get it all. And a pretty good selection of lenses that all have good to excellent reputations.

The 3003 is not quite a “Holy Grail” since it is possible to actually buy. So for a true Holy Grail desert island set up, I think I’d be wishing for a good 4×5 field camera and a HUGE store of fresh dated Polaroid 55PN film…

Thanks for a fun thought experiment, folks!