Leica too trendy for you? Sick of hearing about the Nikon SP? First, what’s wrong with you? And second, what’s wrong with me? Because I’m sick of them too! Looking for something to spark the moist tinder of my dampened interest in camera-liking, I sat down with the CP writing squad and we spent an hour arguing over our favorite lesser-known rangefinders.

The criteria; our choice rangefinders must be high quality, obscure, and for bonus points, affordable (even if they’re not exactly cheap). We discovered pretty quickly that there are plenty of amazing rangefinders that no one talks about.

Here’s a few of them.

The Yashica Electro 35 CC

At some point in our conversation about obscure rangefinders, one of the writers floated the Yashica Electro. After I’d stopped wretching, I argued that that camera is not only too common, but also too unreliable and too boring to make this list. But then someone mentioned the Yashica Electro 35 CC, and things got interesting.

Described by many camera-likers as a Yashica Electro 35 with a wide angle lens, the Yashica Electro 35 CC is nothing of the sort. It is its own camera in every respect.

Where the more common cameras in the Yashica Electro series are utterly enormous, full of unreliable electronics, and run on irritatingly obsolete batteries which require special adapters, the Yashica Electro 35 CC is tiny, more reliable, and runs on the common PX28 (4LR44) battery. I already don’t hate it. But the compact form (indeed, it’s smaller than the smallest Olympus rangefinders of the 1970s) and the quality of life improvements it offers over its chunkier brethren are just the base cake upon which we pile the whipped cream and cherries of a fun metering mode and a super-fast-and-wide lens. [I’ve noticed my metaphors are getting just a bit out of control, but I don’t want to stop. I hope you like them.]

The camera offers aperture-priority automatic shooting, and exposes film through a 35mm F/1.8 fast prime lens. The auto-exposure mode works well, even if the camera is a bit limited by its inability to shoot in full manual mode. The lens renders sharp and punchy images in all light, and works perfectly as a low-light street cam with its wide-standard field of view and its impressive light-collecting capability. All this combines to make the CC (and its even rarer variant, the CCN) an obscure rangefinder worth owning and shooting today.

Get one on eBay

The Leidolf Lordomat

Next, we have a compact, interchangeable lens, all-mechanical, 35mm film rangefinder camera made in the photographically hallowed German city of Wetzlar? But our next pick isn’t the obvious Leica M3, or any camera made by Leitz. This little gem is the Lordomat, made by Leidolf.

The Leidolf Lordomat encapsulates everything that I love about classic cameras into one tiny machine. It’s unerringly all-mechanical, and every lever, dial, switch, and knob actuates with clockwork precision. Its double stroke film advance lever is so nice, I don’t mind that I have to stroke it twice. Pressing the shutter release results in a near-silent exposure. The lens mount system is interesting and unique. The available Leidolf lenses are excellent, and since they’re coupled to the rangefinder, focusing is fast and accurate. Equally important to me, the Lordomat is an unusually small camera.

All of these facets work to make this gem of a rangefinder sparkle like few others. It’s not as refined as some other cameras from Wetzlar, Germany. But it’s certainly more interesting.

Get one on eBay

The Diax IIa

The only camera on this list that I’ve not personally used, the Diax IIa is too interesting to be disqualified simply because I’ve not held one. But, sadly, this description will be limited by the foolish truth that I’ve never bought one. Actually, wait.

Okay. I just bought one. Expect a full review within the month.

Made by the German firm Walter Voss, the Diax IIa is a visually inelegant rangefinder with a bulbous top plate that houses two separate viewfinders for various focal length lenses. The IIa of 1954 is a reconfigured Diax Ia (from 1952) that adds a rangefinder to that big, bold top plate. The lenses are coupled to the rangefinder, and focused via helicoid, and while there’s a real lack of sample shots populating the internet, I suspect the Schneider-Kreuznach lenses will perform beautifully. I’ll see for myself in a few weeks.

Get one on eBay

The Minolta V2

I had to have a Minolta on this list. I’m a fan, you know? The other writers and I discussed the common Minolta models, like the fantastic Super A or the even more popular Minolta 35. But these cameras’ relative ubiquity struck them from the list. Instead, I’ve chosen the Minolta V2, a quirky rangefinder that I’ve been shooting for the past few months in preparation for a review.

The Minolta V2 has a very specific set of features that make it unique and interesting, packed into a body that squanders that interest. It’s a plain camera, looking blandly similar to the hundreds of other rangefinders made during the 1950s and 1960s. But it’s better than most of them (at least, on paper).

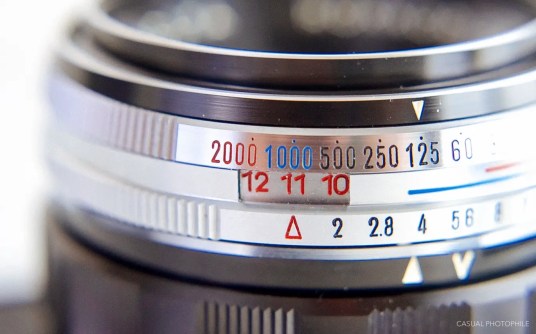

The heart of the machine is a stunningly fast, all-mechanical leaf shutter. With a maximum speed of 1/2000th of a second, the Minolta V2 contained the fastest leaf shutter ever installed in a consumer camera when it debuted in 1958. Its owner’s manual boasted that it was the only camera capable of rendering blur-free speedboats traveling at full throttle. True or not, it’s a fun claim.

Mounted in front of this amazing leaf shutter is an exceptionally capable Rokkor lens. With a focal length of 45mm and a fast maximum aperture of F/2, it’s a perfect do-it-all lens. Images made through this glass are sharp at all apertures, with no light falloff and no chromatic aberration. It’s an uncommonly excellent lens, especially considering its 1958 vintage. If the V2 sounds interesting, buy one now, or wait until my review goes live in a few days. You’ll probably want one after that.

Get one on eBay

The last word in this list comes from the mind of Mike Eckman. Mike’s name may be familiar to some of you, but if it’s not, it should be. He’s the titular figure behind MikeEckman.com, a site that’s overflowing with information on classic cameras. His reviews are incredibly deep dives into the machines we all love (and some that you may never have heard of). If you’ve not yet visited his site, take a look. His pick for an obscure rangefinder doesn’t disappoint. I’ll let him introduce it.

Mike’s Pick – the Clarus MS-35

This is the Clarus MS-35 (full review here), made between the years of 1946 and 1952 in Minneapolis, Minnesota by the Clarus Camera Manufacturing Company. This was the first and only camera ever designed by the Clarus company. Due to infrastructure damage and political upheaval in Germany, camera and lens production came to a halt after World War II, and there was a desperate appetite all over the world for new photographic gear. Established American companies such as Kodak, Wollensak, and ANSCO attempted to fill the void by rushing new and exciting lenses and cameras to market.

Clarus was a new company that attempted to fill the void of a “Leica style” 35mm rangefinder camera with an interchangeable screw lens mount, focal plane shutter, and flash synchronization. The camera had an attractive fully machined all-metal body, top 1/1000 shutter speed, and a comfortable design that placed all of the camera’s controls in easy reach on the top plate. Available for it was a selection of wide angle 35mm to telephoto 101mm Wollensak triplets. On paper, the Clarus went toe to toe with the finest German rangefinders, and with a price of just over $120, it was less than half the cost of it’s primary competition. Of course, being made by a company with no experience making cameras, and built in a country that lacked trained precision engineers, the camera proved to be an unreliable mess. Clarus continually tweaked and updated the design of the camera in the years after it’s release in an attempt to resolve its issues, but its reputation for poor quality and its high price (for an American-made camera) doomed it. Once supplies of German cameras resumed, the demand for cameras like the Clarus MS-35 bottomed out, and in 1952 was discontinued.

Despite its short production run and generally poor reputation, the Clarus remains a fascinating example of the brief period of time when the United States was the top of the camera world. In the hands, the Clarus MS-35 has a solid and robust feel, the ergonomics are quite good, and when working, the shutter gives a satisfying snick as it fires. The Wollensak triplet lenses are quite good and offer incredible value compared to much more expensive five- and six-element lenses produced by other companies. These cameras aren’t exactly rare, but they’re not common. With a generally low selling price, a working Clarus MS-35 is a worthy addition to any rangefinder collection.

That’s the list. Shout at us in the comments if there’s a lesser-known rangefinder you wish we’d included.

You can find lots of cameras for sale at our shop, F Stop Cameras

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Write out one hundred times:

“I don’t need any more rangefinder cameras”

(-:

Wilson