In the world of cameras and optics, few companies are as storied as Leica and Zeiss. Founded in 1846, Zeiss is one of the most enduring manufacturers of anything mechanical anywhere in the world. Leitz is nearly as old, and their Leica camera is as famous as any machine has any right to be. For most photographers, Voigtlander completes the pantheon of optics from the land of shnitzel. But there’s a fourth German optics company that gets far less attention, though it’s nearly as old and just as important.

Schneider-Kreuznach was formed in 1913, and with their impressive resumé, the brand is no lesser god. Unlike Leica, Schneider-Kreuznach has been almost exclusively a lens manufacturer, and the cameras these lenses have fitted to are legendary and varied; Hasselblads, Rolleis, Kodak digital cameras, and even LG smartphones. Schneider-Kreuznach lenses have gone to the moon, and they’ve won an Oscar for technical achievement.

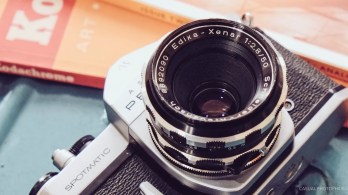

To most photographic enthusiasts, the brand’s small-format lenses are relatively unknown and seldom seen. Indeed, until I purchased my 50mm Schneider-Kreuznach Edixa-Xenar, I’d never even seen one of their M42-mount lenses in person. This is surprising considering that Schneider-Kreuznach made a number of lenses in dozens of focal lengths in 35mm format. We should be virtually falling over Schneider-Kreuznach lenses. But we aren’t, and the brand’s small format lenses are relatively scarce on the secondhand market. That is, unless you look at Kodak Retinas.

The Retina

While Kodak is well-known for quality film, they’re not often remembered as a manufacturer of high-end cameras. Most of the company’s efforts, from the early days of the Brownie and the Pony and on to today’s Kodak branded digital point-and-shoots, have targeted the lower end of the consumer market. Kodak has not habitually chased customers who may have been considering Leica and Zeiss.

Kodak’s only in-house attempt to build a high quality camera ended badly. The Ektra was as expensive as it was unreliable (that means it was lots of both). But if the Ektra crashed and burned in Hindenburgian fashion, the brand’s only other high quality camera soared like a rocket. For three decades, the cameras in the Kodak Retina series produced by Nagel Camerawerks in Germany were quite possibly the best 35mm cameras to come from an American company. And this was in large part due to their excellent Schneider-Kreuznach lenses.

Kodak purchased Nagel Camerawerks in 1931, and commenced Retina production in 1934. Production was halted when some uppity Germans decided to turn most of Europe into a much worse place for everyone, and resumed at the end of the Second World War. In all of their many forms, Kodak Retinas remained in production until 1969.

All of the folding Retinas are quintessentially German. In much the same vein as a vintage Mercedes-Benz, they are beautifully made assemblages of precision engineering. But like a vintage Mercedes, the Retinas are defined almost as much by their compromises as their merits. For Mercedes, these compromises usually came in the form of an underpowered engine. For the Retina, the compromises amount to an array of bizarre ergonomic choices.

While my Retina Ib is my favorite camera to hold and fiddle with, its ergonomics make it tricky to shoot. My principal complaint comes from the toothed edge of the shutter speed selector. This arrangement tethers the aperture selector to the toothed wheel with a little arm on the bottom of the lens barrel. It’s designed so that the user can set a numeric exposure value and then decide if a higher or lower shutter speed is required while maintaining a constant EV.

In practice, it’s infuriating. This little piece of forward thinking means flipping the camera over every time you adjust the shutter speed for a new lighting condition. A one-stop movement of the shutter speed causes an equal and opposite one-stop movement of the aperture arm to maintain the EV. While this keeps the EV constant, in most situations, that’s not what we’re looking for in a manual camera.

If you’re shooting in consistent light, the Retina can be a real treat. If you tend to weave your way down city streets where the light between the buildings is constantly changing, the Retina will only induce rage. Wide latitude films can help minimize this issue, but even the most forgiving films can only take you so far.

This is a shame, because apart from this frequent annoyance, the camera does virtually everything else I like a camera to do. It’s small (smaller than a Canonet in fact), durable, and equipped with a fantastic lens. For years that Schneider-Kreuznach 50mm lens kept me coming back to the Retina despite its flaws.

Fortunately for me, Schneider-Kreuznach produced a nearly identical lens in M42 mount. Rather than tolerating the Retina’s quirks, shooters can easily enjoy this optic on anything from a Spotmatic to a Sony A7, and that is a very good thing.

The Edixa-Xenar 50mm f/2.8

The Edixa-Xenar lenses are deceptively uncomplicated. Both the Retina Ib’s lens and the M42 lens has four elements in three groups in a Tessar-type design. Both use roughly the same focusing design. Where the two differ is in the position of the shutter and the layout of the aperture.

Construction of the M42 mount lens is quite traditional, with a conventional five-bladed aperture actuated by a rear-mounted lever. The Retina lens has a Compur-Syncro leaf shutter mounted behind the removable front element, and a ten-bladed aperture diaphragm mounted aft of that. From what I’ve been able to find, the basic internal designs of the two lenses are very similar.

Though both are elderly (the Retina is from the mid-1950s and the M42 mount lens is from the mid-1960s) both seem to have unusually good coatings. I’ve never noticed any appreciable color fringing, and neither seems prone to flaring even in difficult lighting conditions. While the M42 lens has a built-in “hood” because the front element is set so far back, the Retina does not, but even without the built-in hood there’s nothing to worry about.

The M42 mount lens lacks the watch-like quality found on the Retina. While the focus and aperture rings are well damped, the overall feeling of the lens body is not as high quality as some contemporary lenses and the overall design feels a little clunky when compared to ergonomically superior Super Takumars. The aperture ring on the M42 lens is coupled to a moving DoF indicator, which is visible under a ring of clear plastic. It’s a little kitschy, and fifty years on this piece of plastic can make the cloudy window a bit tricky to see through.

These complaints are relatively minor considering what the lens is capable of in actual use. In-focus areas are almost punishingly sharp, and colors are rendered extremely vividly. If you’re looking for more punch out of color negative film, this lens might be an excellent choice. Blues in particular can become almost comically saturated, and yellows are abnormally punchy. For shooters who prefer a more desaturated look, this lens is sure to annoy.

Bokeh is extremely subjective, and I happen to like the effect produced by the Schneider shot wide open. Rather than creating a sea of blur and bokeh balls, the Schneider produces a very nuanced and textural effect in the out of focus areas. To my eyes this effect creates a lot of depth if used correctly, but quickly becomes distracting with a busy background.

Shots in the samples gallery were made with Kodak Ektar and Ilford HP5 Plus.

Takeaways

Because of its low speed the lens is ultimately less versatile than a similarly priced 50mm f/1.4 from Minolta, Nikon or Pentax. Despite that, its wonderful clarity and vivid color rendition might speak to some shooters. Because its look is so distinct, it’s hard to recommend this lens as a must-have for all shooters. I really enjoy it, and often find myself using it rather than one of the faster fifties in my collection, due solely to its characterful rendering.

Indeed, when I photographed the Kodak Retina for this review I picked up the Schneider and affixed it to my Fuji X series. Even on a crop sensor it can be a remarkably useful piece of glass.

In a sea of 50mm lenses that all do roughly the same thing and produce similar looking images, the Schneider stands out not only because it avoids many vintage-lens pitfalls (it doesn’t vignette, it’s sharp corner to corner, and it’s weirdly flare resistant) but most notably because it makes images with an incomparable look. Not many affordable 50mm lenses produce such distinctive and unique images, but this little Schneider does, and that must be worth something.

Want to shoot this Schneider glass?

Get the lens on eBay

Get a Kodak Retina on eBay

Buy from our own F Stop Cameras

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

The coupled aperture and shutter speed never bothered me. The main irritation with the shutter to me was that if it was set to either the extreme fast or slow end, you would need to move it to give yourself more range and then make your selection. Still I love the Retina for all it’s weirdness (I have the IIIc) and the lens is just fantastic. I use mine now as a second cam to my Leica when I need another film.