Annie Leibovitz is the most recognizable name in modern photography. Not only does the average person recognize her name, but most know her work; the Yoko Ono and John Lennon photo taken right before his assassination, the Demi Moore pregnancy photo. Shoppers standing bored in the grocery checkout have for decades seen her work on the covers of magazines like Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair, and in an era in which the quantity of photographers grows, making true talent more difficult to spot, her portraiture manages to always stand out.

Because of this mainstream recognition, some photographers seem reluctant to cite her as an influence. I am not one of those people. At different points in my childhood I had subscriptions to both Rolling Stone and Vanity Fair and always looked forward to her portrait work. I was personally pleased when I read that she began shooting with the same camera I first used when getting into film – the Minolta SRT-101, and was hugely relieved when I read that she doesn’t tell people to smile when she photographs them. Needless to say, I’m a fan.

So imagine my pleasure when a billboard on I-95 in South Carolina announced an Annie Leibovitz photo exhibition at the Columbia Museum of Art. Considering myself lucky for being in the right place at the right time, I stopped, prepared to see a collection of Leibovitz’s famous portrait work.

But the exhibition was nothing like I expected. Pilgrimage – in both exhibition and book form – is a different kind of Leibovitz, one wholly focused inward and on the people and places from which she gathers inspiration. Made of photographs taken during a time when life had become too busy and demanding for Leibovitz, and spurred by two young daughters unsatisfied with a lack of face time with their mother, she took a break from her usual work, and a vacation with her kids.

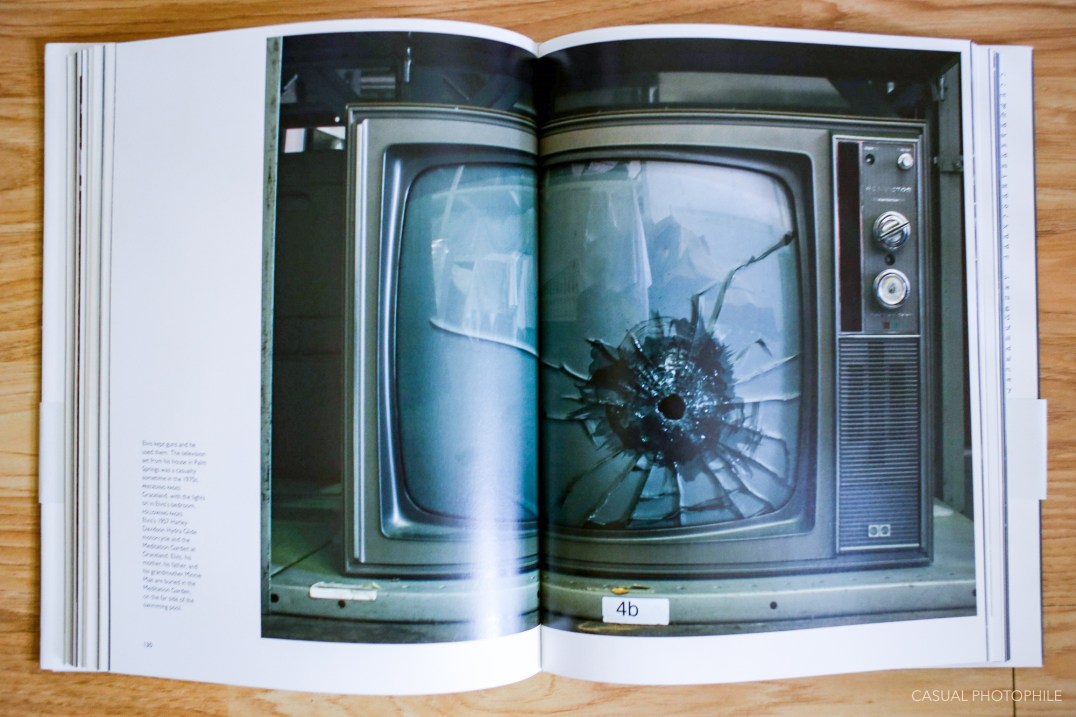

The result is a book of photographs, not of portraits of famous people, but of places and things that meant something to her personally. Pilgrimage takes Leibovitz across thousands of miles as she photographs a wide gamut of historical locations and personalities. There’s Gettysburg and the gloves worn by Abraham Lincoln when he was shot. Virginia Woolf’s writing table, Thoreau’s bed, Emily Dickinson’s dress, Elvis’s motorcycle and the television through which he fired a bullet. These are all items and images that define Leibovitz’s inspiration and, in some way, her creative vision. Pilgrimage is a reaction to feeling the photographer’s creative vision threatened by the repetition and speed of modern life. The exhibit and the book is her journey to reset.

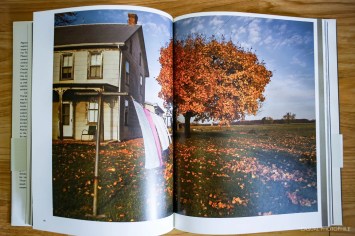

I bought my copy from a local bookstore because seeing the exhibit left such an impression. Like with most photo books, there’s a story here, but truthfully, Pilgrimage did a better job of that in the gallery than it does as a book. The sad result is that I rarely look through it. I don’t like it’s design, and the position of most photos across a two-page double truck is disjointing. The big crease in the middle of the photos really distracts from any message that may have been contained in the original image, and it seems almost a laughably poor decision to display photos this way.

And the actual imagery within these pages is, for me, rather hit and miss. I’m about as uninterested as is possible in the shots that seem like nothing more than product photography; Lincoln’s gloves and nature samples taken by John Muir – even if I recognize their historical importance. The photos I enjoy the most are the ones I have a personal connection to. The shots of Jefferson’s Monticello, because they were made just an hour from my house, and Gettysburg, a place I’ve visited more than any sane person should. But I wouldn’t call these images Earth-movers. They’re there and they’re technically gorgeous, and that’s about the most I can say about them.

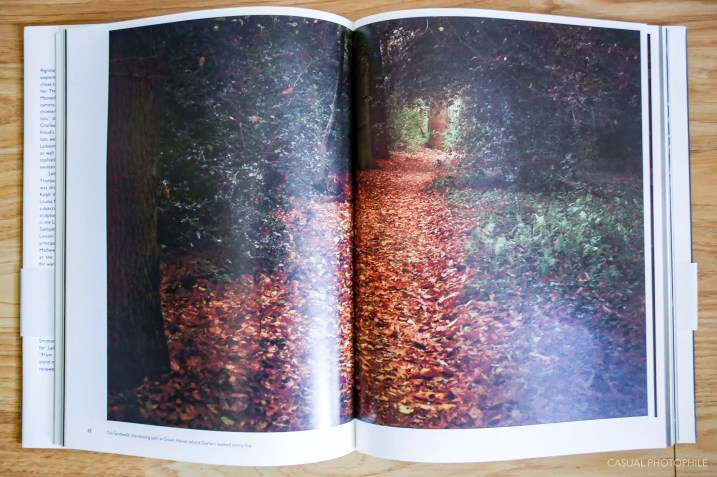

These qualms noted, the landscapes in this collection are truly stunning. Images of Freshwater Bay in Isle of Wight, the view out of Emerson’s bedroom window, and the wilderness around Pete Seeger’s cabin are shot in a way that could’ve only been managed by someone approaching the landscape genre with a fresh eye.

But like all photo books, Pilgrimage is the sum of its parts and should be interpreted as such. This is one of the world’s most visible photographers doing something completely different for their own benefit. Most of us dream of having the sort of access and gigs that Annie Leibovitz has, so imagining her in a sort of creative rut can be hard to believe.

For me it’s immensely relieving. If Annie Leibovitz occasionally struggles in photography, it’s more than okay that I occasionally struggle. That understanding isn’t why I went to see Pilgrimage, the exhibition, but it’s certainly why I own the book.

Want the book?

Buy it on Amazon

Buy it on eBay

Buy it from B&H Photo

Follow Casual Photophile on Facebook and Instagram

[Some of the links in this article will direct users to our affiliates at B&H Photo, Amazon, and eBay. By purchasing anything using these links, Casual Photophile may receive a small commission at no additional charge to you. This helps Casual Photophile produce the content we produce. Many thanks for your support.]

Nice to see a different side of Leibowitz, that she is not painted into a corner. Or should I have said ‘nobody puts Baby in a corner!’

Great read Jeb.